The residue of an angry and vengeful divorce can block stepfamily integration for years or forever. The re-arousal of the old emotional attachment to an ex-spouse, which characteristically surfaces at the time of remarriage and at subsequent life cycle transitions of children, is usually not understood as a predictable process and may therefore lead to denial, misinterpretation, conflict, cutoff, and emotional reac- tivity. As with adjustment to new family structures after divorce, stepfamily integration requires a mini- mum of 2 or 3 years to create a workable new structure that allows family members to move on emotionally.

Forming a remarried family requires a different conceptual model. When there are children, they are a "package deal" with the spouse. This is, of course, always the case with in-laws as well, but not in such an immediate way, since they do not usually move in with you! At the same time, just because you fall in love with a person does not mean you automatically love their children. So how do you take on a new family in mid-journey just because they are there and part of your spouse's life? That is often the hardest part of the bargain. The first thing is to conceptualize and plan for remarriage as a long and complex pro- cess. While more advance planning would be helpful also in first marriages, it is an essential ingredient for successful remarriage, because so many family relationships must be renegotiated at the same time: these include grandparents, in-laws, former in-laws, step-grandparents and stepchildren, half-siblings, etc. (Whiteside, 2006). The presence of children from the beginning of the new relationship makes establishing an exclusive spouse-to-spouse relation ship before undertaking parenthood impossible.

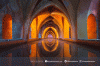

The prerequisite attitudes listed in Figure 22.1 are necessary for a family to be able to work on the developmental issues of the transition process. If, as clinicians, we find ourselves struggling with the fam- ily over developmental issues before the prerequisite attitudes have been adopted, we are probably wast- ing our efforts. For example, it is very hard for a par ent to help children remain connected to ex-in-laws who were never close or supportive unless the parent has fully embraced the new model of family. Much education and discussion may be required before a client can put into effect ideas that may seem counterintuitive, aversive, or time-consuming.

The relationship of the children and steppar- ent can evolve only over time as their connection develops and as an extension of the child's bond with the original parent. Stepparents can only gradually assume a role, hopefully friendly, as the partner of the child's parent. Unless the children are young at the time of the remarriage, the parent-and-child para- digm may never apply to the new parent. This is a life cycle reality, not a failure on anyone's part. Indeed, in the "othermother" research of Linda Burton and her colleagues, poor women are often especially resentful of raising someone else's children unless they have a special proclivity, perhaps from family of origin experiences to be a parent figure (Burton & Hardaway, 2012).

Predictable Issues in Remarriage Adjustment and family integration issues with stepparents and stepchildren

The stereotypes of stepparents are deeply blaming. Most difficult of all is the role of stepmother. The problem for her is especially poignant, since she is usually the one most sensitive to the needs of others, and it will be extremely difficult for her to take a back seat while her husband struggles awkwardly in an uncomfortable situation. The fact is that she has no alternative. Women's tendency to take responsi bility for family relationships, to believe that what goes wrong is their fault and that, if they just try hard enough, they can make things work out, are the major problems for them in remarried families, since the situation carries with it built-in structural ambiguities, loyalty conflicts, guilt, and member ship problems. Societal expectations for stepmoth- ers to love and care for their stepchildren are also stronger than for stepfathers. If stepfathers help out a bit financially and do a few administrative chores, they may be viewed as an asset, even though that is not a satisfactory parental role. But the expectation for stepmothers is that they will make up to children for whatever losses they have experienced, which is, of course, impossible. Clinically, it is important to relieve them of these expectations.

A stepmother's ambivalence about her parent- ing role tends to be particularly acute when step- children are young and remain in the custody of her husband's ex-wife. In this common situation, stepmothers tend to be less emotionally attached to the children and to feel disrupted and exploited during their visits. Meanwhile the husband's co- parenting partnership may appear to be conducted more with his ex-spouse than with her. Conflicting role expectations set mothers and stepmothers into competitive struggles over childrearing practices. It appears to be better for stepmothers to retain their work outside the home for their independence, emo- tional support, and validation. In addition to contrib- uting needed money, it makes them less available at home for the impossible job of dealing with the husband's children.

Along with finances, stepchildren are the major contributor to remarriage adjustment problems. Remarriage often leads to a renewal of custody diffi- culties in prior relationships. Families with stepchildren are much more complicated and twice as likely to divorce. Marital satisfaction is correlated with the stepparent's connection to stepchildren. Although the remarriage itself might be congenial, the presence of stepchildren often creates child-related problems that may lead the couple to separate. Some stepparents do not even consider their live-in step- child as part of the family, and stepchildren are even more likely to discount their live-in stepparents. Stepchildren are much more likely to change residence or leave home early than biological children. Children in stepfamilies may appear to have more power than children in first families, although they experience less autonomy than in the single-parent phase, where they typically have more adult privileges and responsibilities.

Stepparents need to take a slow route to parent hood, first becoming friends with their stepchildren, and only gradually assuming an active role in parent ing. It generally takes at least 2 years to become comanagers of their stepchildren with their spouses. For stepparents to compete with their stepchildren for pri- macy with their spouse is inappropriate, as if the couple and parent-child relationships were on the same hierarchical level, which, of course, they are not.

Stepfathers may get caught in the bind between rescuer and intruder, called upon to help discipline the stepchildren and then criticized by them and their mother for this intervention. Over-trying by the new parent is a major problem, often related to guilt about unresolved or unresolvable aspects of the system.

Overall, mothers, daughters, stepdaughters, and stepmothers experience more stress, less sat- isfaction, and more symptoms than fathers, sons, stepsons, and stepfathers. Stepmother-stepdaughter relationships tend to be the most difficult of all. Daughters, who are often closest to mothers in divorce, tend to have a lot of difficulty with stepfa- thers, no matter how hard the stepfather tries. Girls' stress probably reflects the fact that they feel more responsible for emotional relationships in a family and thus get caught between loyalty and protection of their mothers and conflicts with their stepmothers. While divorce appears to have more adverse effects for boys, remarriage is more disruptive for girls. Boys, who are often difficult for a single mother, may settle down after the entry of a stepfather.