Keynes' general wisdom regarding fiscal policies is to adopt countercyclical measures in response to fluctuating economic cycles: contractive during periods of boom to avoid overheating the economy and expansive during periods of recession to bolster economic activity. However, due to frequent external shocks as a consequence of increasingly complex global economic integration, emerging markets and developing economies -- especially commodity exporters -- tend to amplify the fluctuating cycle, by implementing procyclical fiscal policy. The degree of fiscal procyclicality in commodity dependent countries is twice above non commodity exporters (World Bank, 2023). How can these countries fail to control the supposedly stabilizing 'fiscal' measures? How much of an impact can it bring towards countries' economy? What does this imply for commodity exporters? It turns out that political-economy pressures as well as credit inability in worsening economic situations could be key to explaining this fiscal spiraling phenomenon.

Stabilizing the economy

Fiscal policy is the use of government spending and taxation to influence the economy (IMF, 2022). Fiscal policy is often used by governments to encourage robust, long-term growth and to lower poverty. Prior to the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, monetary policy played a more prominent role in macroeconomic stabilization. However, during the GFC, liquidity traps suffered by big economies like the US, Europe, and Japan made monetary weapons less effective -- leading to no choice but to conduct a fiscal policy expansion. After the GFC, countercyclical fiscal policy has become more eminent, especially in matters of stabilizing macroeconomic conditions.

ECB chief economist Philip Lane stated how countercyclical fiscal policy is preeminent. First, it could boost the economy during a downturn and prevent it from overheating during a boom. It is a responsible option given that it is unclear if the crisis will be a temporary or lasting shock. Second, a countercyclical fiscal policy, by requiring the government to limit spending during a boom, could contain the absolute level of spending due to political economy factors like corruption. Third, the automatic stabilizer component of a government budget allows it to pursue countercyclical fiscal policy (Lane, 2002). However, it remains the issue that developing countries that export resources as its main source of revenue still tend to adopt procyclical fiscal policy.

Stabilizing? Not entirely

For emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), it is still the case that procyclical policy amplifies an already volatile business cycle (more emphasis on emerging markets).

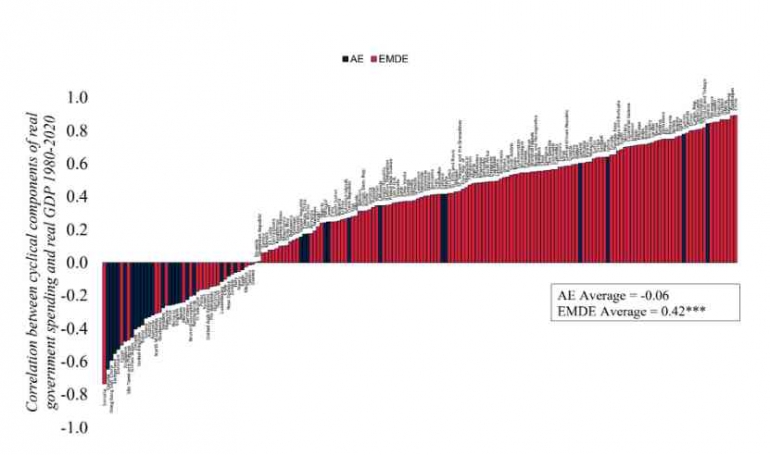

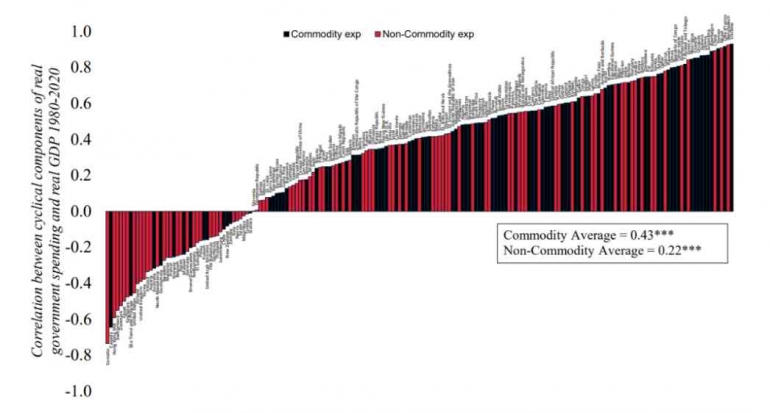

Figure 1 shows the correlations for the procyclical components of GDP and government spending for 189 countries, mixed between advanced and developing economies, from 1980 until 2020. This visual representation is undoubtedly salient, as we can see a dominating amount of positive correlation (indicating procyclicality) in developing countries. An even more striking correlation is shown between commodity exporters and non-commodity exporters in this regard. Figure 2 reveals that the association between the cyclical components of real government spending and real GDP for commodity exporters is twice as great as that for non-commodity exporters (0.43 compared to 0.22, both highly significant). The result still holds in 3 main commodities exported, namely agriculture, metals, and energy, which means that commodity exporters, regardless of their major commodity export, are more likely to deploy procyclical fiscal policy in response to booms and busts.

How does this happen? Government spending frequently spirals out of control in prosperous times, leading to the inability to borrow in difficult times which doubles its volatility and hurts the economy for commodity dependent EMDEs. In contrast to what Keynes envisioned as a stabilizing tool, fiscal policy thus became a source of instability for certain countries (World Bank, 2023).

Given the notable reaction of fiscal variables to commodity shocks, the function of fiscal policy as a potential source of macroeconomic instability is particularly pertinent in commodity exporters. This analysis is evident in an early policy analysis comparing five developing countries (Colombia, Cameroon, Kenya, Nigeria, and Jamaica) when facing commodity price booms in 1970. Fiscal authorities in Kenya, Nigeria, and Jamaica all lost control over public finances, resulting in a sharp increase in government spending as a percentage of GDP. The increase in spending actually exceeds the growth in revenue, which generally results in increased borrowing from abroad and bigger budget deficits. This lack of budgetary control commonly led to full-blown fiscal crises (Cuddington, 1989).

The game of managing abundance

In the same case of the 1970 coffee boom, Colombia and Cameroon experienced a different outcome from the other 3 developing countries mentioned. The 2 countries managed to avoid large increases in fiscal revenues and government expenditures, hence lifting their feet just in time from long term structural problems. Colombia and Cameroon won at one game to escape this fiscal crisis as a commodity producer: the game of managing abundance. Policymakers and economic analysts in commodity dependent countries frequently have serious concerns about this notion of managing abundance (World Bank, 1989).

Managing abundance is obviously the mirror image of fiscal cyclicality. A nation that successfully avoids spending more of its resources than it gains will be pursuing a countercyclical fiscal policy, and vice versa. Cameroon's government spending associated with the coffee boom was modest, but whether this policy moderates the spending effect of the boom depends on how the government uses the additional resources. In the case of Cameroon, government spending was restrained in order to generate significant public savings. A big portion of the windfall was then invested in domestic capital production, reducing the need for external borrowing in bad times -- which is key to explain why Cameroon survived while others didn't.

Frictions in international capital market

One of the most well-known macroeconomic elaborations of procyclicality is to assess the different imperfections that may cause inability for commodity exporters to borrow during difficult times. The Lack of access to foreign credit markets during recessions will give fiscal policy a procyclical bias since the fiscal authority will be forced to cut spending or raise taxes in order to finance a primary deficit.

The macroeconomic application of capital controls over the business cycle is a policy-induced friction. As well known, the IMF supports adopting capital controls as a last resort. If they are used in good economic times, capital controls are most likely to be used in bad economic times as well. Binding capital controls in difficult times will inevitably make it difficult for the fiscal authority to maintain consistent tax rates or government spending over the course of the business cycle, which will result in procyclical fiscal policy.

Political economy factors: Closer than we think

Another key factor to explain this phenomenon is by taking account of political economic frictions in commodity dependent countries. Certain fiscal claimants (ministries, provinces, unions, etc) strive to seize resources in good times without seeing its impacts on other claimants, known as the voracity effect. This voracity effect, combined with the institutional problems surrounding developing countries, brings massive impact on its fiscal cyclicality.

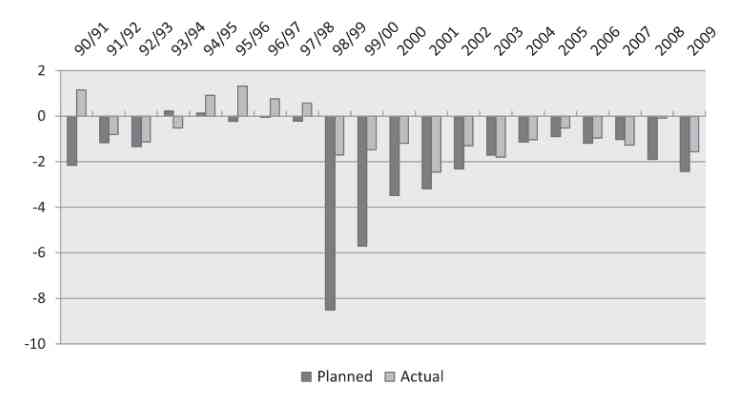

Looking at Indonesia's situation, it is increasingly difficult to deal with its weakening budget executions. This is explained by seeing the large gap between the planned budget and the realized budget in Indonesia in Figure 3. A poor ability to carry out the budget will make fiscal policy less effective at supporting aggregate demand. If we examine closer, the figure also reflects a weak budget financing capacity, especially during recessionary times like the late 1990s (the AFC) and late 2000s (the GFC).

This clearly shows how difficult it is for developing countries like Indonesia to borrow during difficult times. Indonesia experiences liquidity problems, which make it more difficult for the government to expand the budget during economic downturns. According to an IMF report (IMF, 2009), during the GFC in late 2008, Indonesia's borrowing costs, as measured by the Emerging Market Bond Index (EMBI) and Credit Default Swap (CDS), spiked to nearly 1,200 basis points (bps), significantly higher than those of its peers Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. The Indonesian government is discouraged from using the international financial market to finance fiscal expansion during downturns due to higher borrowing costs.

Essentially, the cyclical components (automatic stabilizers) of developing countries' budget structure is very limited compared to many advanced economies. The absence of transfer schemes in response to changing economic cycles contributes to this factor. Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a refundable tax credit for low-wage workers in recessionary times, is one of these transfer schemes deployed by developed countries as a fiscal stabilization tool. This kind of scheme is rarely seen in developing countries, definitely not in Indonesia. Indeed, there was a cash transfer program (Bantuan Langsung Tunai) in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic that was similar in the sense that it subsidizes wages for workers that were laid off. However, it was a transitory and short-term initiative with the primary goal of compensating civil servants that were affected, which was too little too late to deal with the fluctuating economic cycle -- also ultimately revealed to be corrupted.

Without adequate economic stabilizers, there would be consequences in the policies deployed in economic cycles. Inside lags from the delay of government fiscal intervention (long periods of legislation), and outside lags from the delay of government monetary invention -- typically because of the long economic integration. These unprecedented consequences would make it even harder for commodity exporters in bad times. This shows how political infrastructure plays a huge role in this continuous issue.

When it rains, it pours

Inevitably, commodity exporters' inability to manage abundance in good times, caused by factors like political and capital market infrastructure, explains why it is difficult to deploy countercyclical fiscal policy even until now. When it rains, it pours. When one negative thing happens, a worse effect follows. When commodity prices fall, governments -- that have fallen into the temptation of spending out of windfalls -- will ultimately suffer as it increases their inability to borrow during bad times. This fiscal procyclical trap amplifies an already volatile business cycle of commodity exporters. Governments should be more aware of the fluctuating economic cycles and increase the quality of political institutions to prevent structural crises. Integrity of decision makers in developing countries ought to be mended if this were to change. As Friedman once said, "Governments never learn; only people learn."

Michael Abimanyu Kaeng | Undergraduate Economics Student at the University of Indonesia | Staff of Economic Studies Division at Kanopi FEB UI

Bibliography:

ABDUROHMAN, & RESOSUDARMO, B. P. (2017). The behavior of fiscal policy in Indonesia in response to economic cycles. The Singapore Economic Review, 62(02), 377-401. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0217590816500041

Arroyo Marioli, F., & Vegh, C. A. (2023). Fiscal Procyclicality in commodity exporting countries: How much does it pour and why? World Bank Policy Research Working Papers. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-10428

Bauducco, S., & Caprioli, F. (2014). Optimal fiscal policy in a small open economy with limited commitment. Journal of International Economics, 93(2), 302-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2014.04.001

Cariolle, J. (2017). The voracity and scarcity effects of export shocks on bribery. SSRN Electronic Journal, fondation pour les tudes et recherches sur le dveloppement international . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3032914

Cuddington, J. (1989). Commodity export booms in developing countries. The World Bank Research Observer, 4(2), 143-165. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/4.2.143

Lane, P. R. (2003). The cyclical behaviour of fiscal policy: Evidence from the OECD. Journal of Public Economics, 87(12), 2661-2675. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0047-2727(02)00075-0

Mark Horton. (n.d.). Governments use spending and taxing powers to promote stable and sustainable growth. IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Back-to-Basics/Fiscal-Policy

Nichols, A., & Rothstein, J. (2015). The earned income tax credit (EITC). https://doi.org/10.3386/w21211

Sugawara, N. (2014). From volatility to stability in expenditure: Stabilization funds in resource-rich countries. IMF Working Papers, 14(43), 1. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781475515275.001

Tornell, A., & Lane, P. R. (1999). The voracity effect. American Economic Review, 89(1), 22-46. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.1.22