"In the casino, the cardinal rule is to keep them playing and to keep them coming back. The longer they play, the more they lose, and in the end, we get it all."

Columella, a prominent writer on Roman agriculture from the 1st century AD, wrote down his complaint about how his devotees would often bet on cockfighting with all their inheritance. His little demur denoted how gambling walked along mankind through its history as it still lives by today, despite being regarded as reprehensible in some ethical sense. The origin of probability itself came from two mathematicians, Pierre de Fermat and Blaise Pascal, solving a gambler's dispute in 1654. There was no doubt that gambling affected civilization, as if it was designed to be appealing to us.

While there's a whole classification of mathematical formulas generated for gambling itself, this essay wants to point out how participants of gambling, as individuals, choose to become a part of it. Neoclassical economics assumes everyone acts rationally and chooses the most optimal decision all the time. Humans, however, as we know, do not constantly act rational; they're prone to errors and are subject to emotional impulsivity. This statement aligns well with one of the most interesting gambling-related questions of all: Why do the majority of gamblers even gamble at all? Even moreso, why do most of them still continue to do so, even though, on average, they lose money? (Stetzka, 2021).

Defining Rationality (and Irrationality)

Dispute runs on the topic of the rationality of gamblers, but what defines rationality and irrationality might be more limited and specific in this context. Rationality in this term is defined as consistent utility-maximizing behavior from a person acting in their best interest. There's also the term "bounded rationality", meaning people with sufficient cognitive ability, information, and time do not always make the "most correct" choice from an economist's perspective. Despite enough information being available to them, individuals with bounded rationality tend to go with their "guts" as they can't process a lot of information in such a short window of time.

Irrational acts, on the other hand, can be defined as inconsistency, being misled by manipulation and deception that suffer from a loss of control of their behavior. Loss of control has been identified as the main driver of problem and pathological gambling (Stetzka, 2021).

In terms of rationality, many arguments have associated gamblers with both ends of the spectrum. For example, there is evidence on gamblers that make money from gambling using sophisticated strategies, or insider information (Stetzka, 2021). These gamblers can be considered rational, almost associated with the same pathway of thinking like those of rational financial investors. Furthermore, the market outcomes in gambling and betting markets suggest that there must be high levels of sophistication and sound economic reasoning behind many gamblers' decisions, like those who use odds as predictors for the outcomes (Ibid.).

On the contrary, a fraction of gamblers had been found to end up in the worst consequences of gambling, such as divorce, job loss, debt, and even imprisonment---most of which are the results of loss of control while gambling. The irrationality of some individuals that stems from overconfidence, loss aversion and self-control (or lack thereof) became the foundational concept of behavioral economics today. Although irrational, this behavior is actually very common and can be explained through some basic concept of behavioural economics.

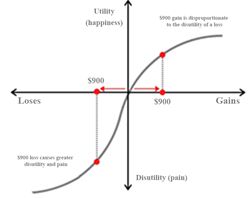

Prospect Theory: The Reason Behind Gambling Streaks

Let's do some thought process to better understand one of the key theories in understanding behavioral economics. Say you can choose between getting $900 dollars for free or taking a 90% chance of winning $1000 (therefore also a 10% chance to win nothing), what would you choose? Most people would choose $900 to avoid any risk, even though the expected outcome is the same for both options. But if I asked you to choose between losing $900 and taking a 90% chance of losing $1000, which one would you choose? Even though both options have the same expected utility, most people would probably prefer the latter of the two, the risk seeking option, in hope to avoid the small chances of loss. This behavior, otherwise known as "loss aversion", is at the core of prospect theory and how we make decisions pertaining to risk.

Introduced by Amor Tversky and Daniel Kahneman as a descriptive model of risky decision-making, prospect theory describes an influential phenomenon called "loss aversion": the natural tendency to respond more strongly to losses than gains when people evaluate risky choices. According to the theory, individuals don't use objective probabilities in their calculations but weighted ones based on what is perceived as loss and gains. If someone faced a risky choice leading to gains, they become risk-averse, preferring the choice with higher certainty. But if someone faced a risky choice leading to losses, they become risk-seeking, preferring the choice that actively avoids losses.

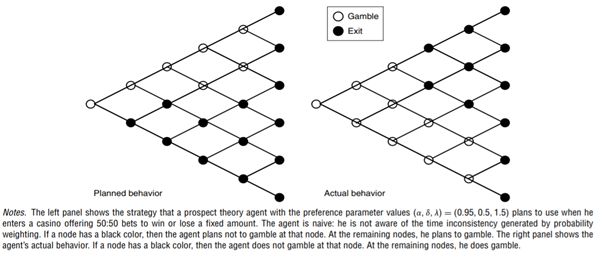

A research done in 2012 by N.C. Barberis that modeled the behavior of a casino gambler based on prospect theory can give a broader picture on how it is displayed in real life gambling. In this scenario, a casino gambler enters the casino to gamble at the offer of 50:50 bets and the plan to leave when faced with losses and stay while winning. Contrary to their original plan, the gambler kept on updating their beliefs about their chances of winning and losing. They gambled as long as possible when losing and stopped once they accumulated some gain, therefore capturing the point that was made in the previous paragraph, namely, that people often gamble more than they planned to in the region of losses (Barberis, 2012).

Gambler's Motives

Though some inconsistency doesn't always mean they are irrational, some regard them as bounded rationality. A gambler displaying boundedly (ir)rational behavior still has enough self-control to keep their losses from gambling within acceptable limits by societal standard. One example showcasing bounded rationality can usually be found in slot machine gamblers. They believe that their gambling abilities are much more skillful than they actually are. This can be interpreted as a cognitive limitation as they're unaware of the functionality of the machine or the randomness of wins and losses, already programmed to exploit the heuristic decision-making pattern of the gambler by the casino running it.

However, regular gamblers of slot machines don't try to maximize their profit. Instead, they gamble with small stakes with the objective of maximizing their time spent playing, despite their awareness of losses (Griffiths, 1994). Their incentives to gamble aren't fully financially related, as they "gamble with the money rather than for it". In their case, the act of gambling itself can be interpreted as providing a kind of consumption benefit (Ibid.). When one gambles for the sake of gambling, deriving consumption utility from the activity itself, then it might be counted as rational even when they keep on losing.

Regardless of the theories involved, it is almost impossible to infer one single reason on why people gamble. There's not one definite representative who represents the gambler population as a whole. There are various degrees of rationality and different motives involved, ranging from those deemed as rational with cognitive ability to count as those with financial motives and gains, to irrational gamblers gambling their lives away despite their losses. Whether they want to do so for the promise of effortless money or the fun of gambling itself, the real winners are those who provide gamblers a dinner with 'lady luck' herself.

By Ariella Sassy Kirana Riefita | Ilmu Ekonomi 2021 | Trainee Staff Divisi Kajian Kanopi 2021

References:

- Barberis, N., & He, X. (2011, November 04). A model of casino gambling. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1435

- Bounded rationality in compulsive consumption - uni-hamburg.de. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://www.wiso.uni-hamburg.de/fachbereich-sozoek/forschung/gluecksspielforschung/Dateien/Veroeffentlichungen/bounded-rationality-in-compulsive-consumption-fiedler-gambling-research-working-paper-no-1.pdf

- Boyce, P. (2021, April 14). Prospect theory definition and examples. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://boycewire.com/prospect-theory-definition-and-examples/

- Fiedler, I. (2019, September 21). Bounded rationality in compulsive consumption - uni-hamburg.de. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://www.wiso.uni-hamburg.de/fachbereich-sozoek/forschung/gluecksspielforschung/Dateien/Veroeffentlichungen/bounded-rationality-in-compulsive-consumption-fiedler-gambling-research-working-paper-no-1.pdf

- Gambling. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/gambling

- Griffiths, M. (2011, April 13). The role of cognitive bias and skill in fruit machine gambling. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1994.tb02529.x

- Stetzka, R., & Winter, S. (2021, October 13). How rational is gambling? Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/joes.12473

- Witynski, M. (n.d.). Behavioral Economics, explained. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://news.uchicago.edu/explainer/what-is-behavioral-economics

- World Leaders in Research-Based User Experience. (n.d.). Prospect theory and loss aversion: How users make decisions. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/prospect-theory/

- World Leaders in Research-Based User Experience. (n.d.). Prospect theory and loss aversion: How users make decisions. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/prospect-theory/

Baca konten-konten menarik Kompasiana langsung dari smartphone kamu. Follow channel WhatsApp Kompasiana sekarang di sini: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaYjYaL4Spk7WflFYJ2H