Wealth tax vs. corporate tax cuts, foreign aid for poor countries vs. no foreign aid, free market vs. government interventions. It is not an everyday occasion that people on the left and the right of the political spectrum see eye to eye on grand economics debates like those. But, once in a blue moon they do. This puzzling phenomenon is currently unfolding in the U.S. One idea lies at its center: banning stock buybacks.

In 2019, Democratic Sens. Chuck Schumer and Bernie Sanders called out the act as corporate self-indulgence that "has become an enormous problem for workers and for the long-term strength of the economy". From the right wing, Republican Sen. Marco Rubio has also proposed that the share repurchases be taxed as dividends, instead of capital gains, to discourage this behaviour.

More recently, another Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren unveiled a plan to impose a permanent ban of stock buybacks for companies that receive aid in light of the US airline industry asking for $50 billion of pandemic-induced bailout. In a press conference not long after, President Donald Trump said that he is "strongly recommending a buyback exclusion".

Now, how can we be sure that this isn't just another populist tool used to gain votes? Is there an actual problem looming over it that has escaped our attention? To see why the idea of banning stock buybacks is getting support from politicians of both parties, first we need to see why it might be popular among the people.

Requiem for the American dream

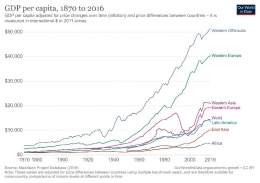

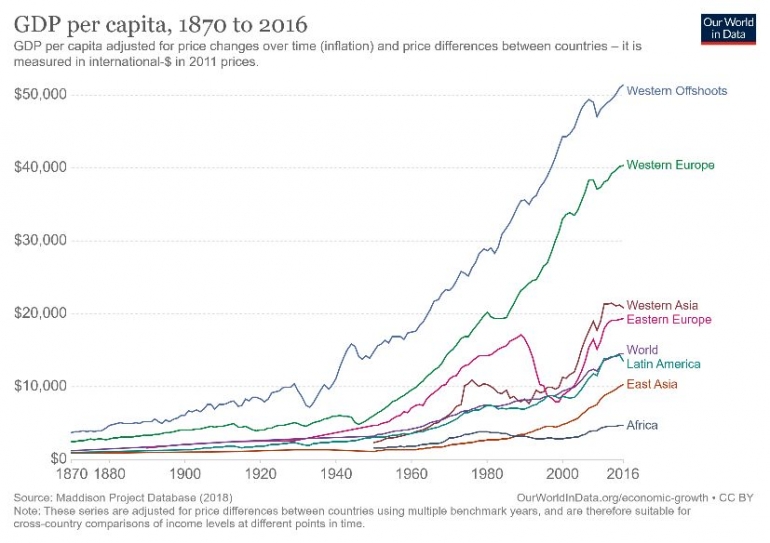

As, arguably, the biggest economy in the world, the U.S. now contributes roughly 25% of the world's GDP. Together with three other countries (i.e., Australia, Canada, and New Zealand) classified together as the Western Offshoots, the U.S. experienced much more rapid growth than the rest of the world since 1820. This translates into a promise of individual wealth and social mobility that lures people into the American dream.

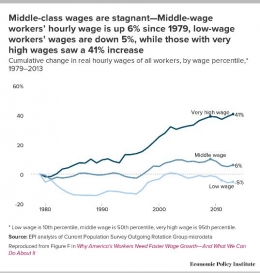

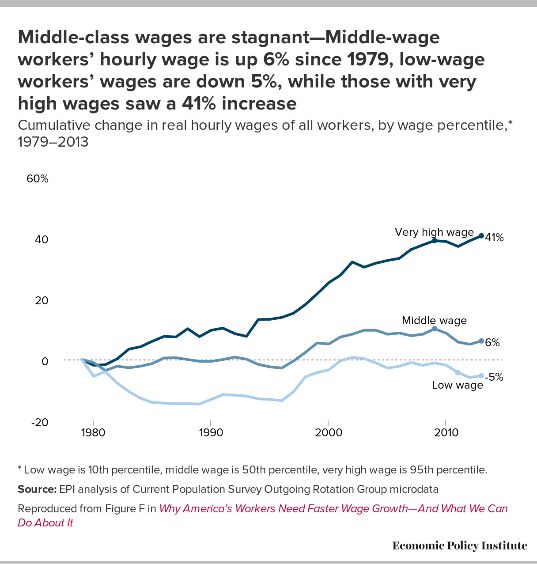

Despite the steadily increasing real per capita GDP, a vast majority of Americans have not been able to turn said dream into reality. The wage of the middle class has stayed the same since 40 years ago, even though their productivity kept rising. According to a senior writer from Pew Research Center, the $4.03 per hour rate recorded in 1973 had the same purchasing power that $23.68 would today.

If so, where has all that promised prosperity gone to? The answer, as the second graph suggests, is to those who already had disproportionately deep pockets to begin with. In 2018, Mishel and Wolfe (2019) found that for every $1 a typical worker earns, a CEO is paid $278.

In contrast, the CEO-to-typical-worker compensation ratio was 20-to-1 in 1965 and 58-to-1 in 1989. Seeing this staggering figure, the word "chasm" might be more befitting to describe it than mere "gap".

Creating the chasm

Some popular hypotheses that tried to explain why these issues surfaced have mostly pointed fingers at globalization and automation. However, there is indeed one other force that we tend to overlook. Benmelech, Bergman, and Kim (2018) revealed that labor-market concentration is the hidden culprit behind this and it explains at least 30% of wage stagnation in the U.S.

A highly concentrated labor market means that there are too few employers competing for the same workers on the local level. When a worker is dissatisfied with their pay, they cannot simply switch to another employer because there is not much choice available. This gives the employers a monopsony power and puts the workers in a weak position to bargain for better compensation.

Essentially, there are some ways in which firms can spend their extra cash: capital expenditures, R&D, buy other companies, or return the money to its shareholders through dividends and buybacks. Over the last decade, S&P 500 companies have spent $5.3 trillion on share repurchases.

The main reason why company executives spent such a generous amount is because 83% of their pay comes from stock-based instruments and short-term buybacks artificially inflate stock prices by boosting earnings per share (Lazonick, 2014).

From 2003 to 2012, those companies used 54% of their earnings for stock buybacks and returned 37% of it to shareholders in the form of dividends. This leaves little space for reinvestment into the companies themselves, including for paying their employees higher salaries.

Lazonick who has studied this matter for three decades concluded that this approach of "maximizing shareholder value" (MSV) has contributed to inequality and instability in the U.S. economy.

Initially, buybacks were banned in the '20s because it led to unscrupulous and speculative activities. But, it made a comeback in 1982 under President Ronald Reagan's ruling. The GOP's 2017 corporate tax cuts from 35% to 21% that was meant to spur reinvestment and create jobs also fuelled a record-high share repurchase.

These policies have exacerbated the imbalanced distribution of power between American workers and their employees. There are only abundant profits without shared prosperity.

Other alternatives

To be clear, stock buybacks per se is not necessarily a bad thing. When the stock is undervalued, executives with a vision of long-term growth can buy them to take ownership into their own hands. Warren Buffett used this kind of buybacks in the 1980s at his company GEICO---now Berkshire Hathaway. Another condition to be fulfilled is that the company must be profitable enough so that real investment plans can be realized.

Admittedly, bringing the U.S. back onto the path of the so-called American dream needs more than just this. There is also the problem of employer-employee power dynamics, which have brought the attention of thousands of scholars---including economists Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Piketty, Dani Rodrik, and Ha-Joon Chang---and made them call for the democratization of work. There is also an idea that is gaining ground of profit sharing to not only shareholders, but also workers. An already popular and less radical idea would be to raise the minimum wage.

However, those are ideas for future discussions. For now, the U.S. have faced the urgency of declining living standards, support has been acquired from both ruling parties, and there is only one thing left to be done. Ban stock buybacks.

References without hyperlink

Benmelech, E., Bergman, N., & Kim, H. (2018). Strong employers and weak employees: How does employer concentration affect wages? (No. w24307). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lazonick, W. (2014). Profits Without Prosperity. Harvard Business Review.

Mishel, L., and Wolfe, J. (2018). CEO compensation has grown 940% since 1978. Economic Policy Institute.

By Rosalia Marcha Violeta | Economics batch 2018 | Head of Economic Studies Division Kanopi FEB UI 2020

Baca konten-konten menarik Kompasiana langsung dari smartphone kamu. Follow channel WhatsApp Kompasiana sekarang di sini: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaYjYaL4Spk7WflFYJ2H