When I entered FEB UI last year, it seemed to me that the faculty had a strict on-time policy, both in the classroom and outside of it. However, as time went by, I realized that even this acclaimed institute is filled with people who are prone to the very human nature of being late, including myself.

Even though it is merely irritating at the local level, it can do some real damage at the aggregate level of the economy. To provide a picture, a 2006 survey stated that American CEOs' tardiness costs the US economy $90 billion in lost productivity annually while a 2012 study stated that staff lateness costs the British economy 9 billion every year .

Psychology as the study of behavior has offered some explanations as to why people keep doing this, but economics as the study of choice may offer more insight. In this writing, I will present a model that explores what drives a person to become late at coming to an occasion.

Meet the model

The model presented explains how people deviate from being on time for events that have an independent, recurring schedule. In other words, no matter what time people come, the event that happens repeatedly begins at a certain time, uninfluenced whether its attendants come early or late. Seminars, movie screenings, public transportation departures, and classes are examples of events possessing such characteristics.

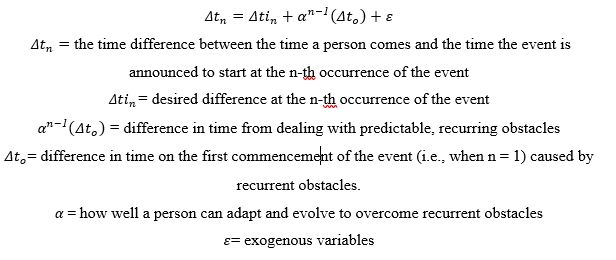

As can be seen in the equation below, the model explains that the time difference between the time a person comes and the time the event is announced to start at the n-th occurrence of the event is the sum of her "desired difference", difference in time from how well she negotiates predictable obstacles hindering her, and exogenous residuals. An avid reader of mathematics may recognize this model as a difference equation. Note that the two first variables are a function of n, meaning that its value may change over time. Therefore, this model not only explains how late (or early) a person can be, but it can also explain how that person adjusts her arrival time intertemporally.

To understand the meaning of "desired difference" (ti(n)), a harsh truth must be grasped: people intentionally do not come on time, let alone come early. Granted, there are good benefits from coming before the event kicks in; after all, an early bird can catch a lot of "worm", such as common goods offered in the event (like a strategic back seat). However, being early incurs an opportunity cost as one can do something else instead of waiting for the event to start, like get more bedtime before a morning class. In addition, Durayappah (2014) highlighted the fact that being early can be uncomfortable and impolite.

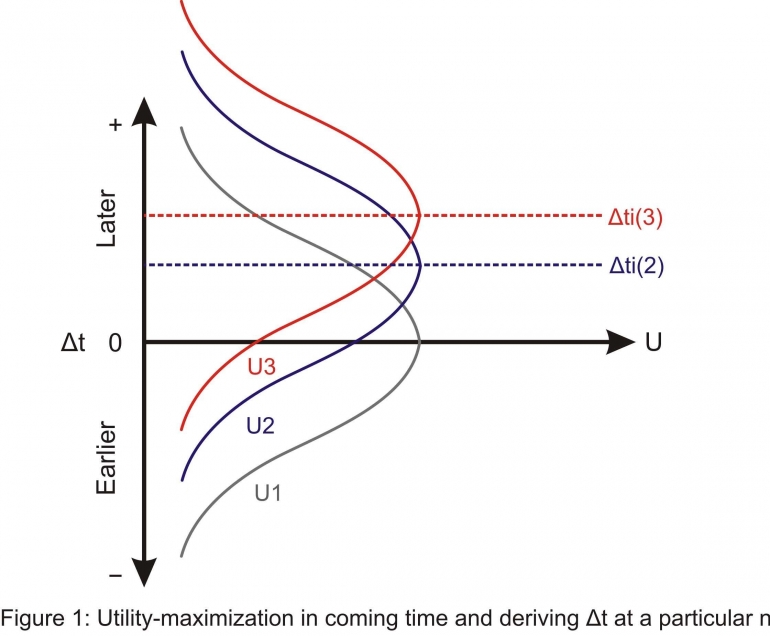

A utility-maximizing person may seek to come in late, up to the point where the utility from being late for an additional minute is equal to the perceived loss of utility from missing the event for that additional minute, as demonstrated in Figure 1 below. If the event is perceived to be on time, then people will seek to come on time like in U1. However, if the utility from the event is perceived to trickle only after some time has elapsed, such as in a cinema where the movie only rolls after some advertisement, then do not be surprised if people seek to come in late, as shown in U2. Based on that assumption, participants to an event do not necessarily have a desire to come at the time its organizers tell them to come.

She then lives up to her name, and when she comes to the next general lecture, she will shift her expectations to U2. If the lecturer is still late, then she might shift her expectations further to U3 and have a bigger desired difference when she attends the event for the third time. For the purpose of simplifying the discussion, it is assumed that the desired difference is upward sloping, although it can take many forms.

The implication of adjustable means that an event organizer (EO) can't fool all the audience all the time. If they tell the audience to come earlier than when they intend to start the event to counter people from being late, some newcomers like Gullible George may buy into it. However, Cynical Cindy may recognize the EO's intentions based on her previous experiences and her understanding of how those EOs conduct themselves and still come late. As a result, even though deceiving the people may work in the short run, their rational expectations will adjust and people will still end up being late.

The lesson is clear; to make sure that desired difference is close to zero in the long run, an EO must make sure that people perceive the events capable of delivering utility worth their time from minute 0. In the case of the general lecture, the EO must get the speaker to start on time even if the auditorium is only filled with one student. This must be painful for the organizers, but that is the price to establish credibility. In the long run, this should lead to people like Cynical Cindy to adjust their desired difference to zero, leading them to want to come on time.

On the way, lying in bed

In addition to participants' desired difference, they can even be tardier due to additional obstacles, represented in . Formally, is the difference in time on the first commencement of the event (i.e., when n = 1) caused by recurrent obstacles.

To understand this concept better, assume that Late Larry plans to come ten minutes late on her first day of college, making . However, as it is his first day, he hasn't figured out how long it might take for him to dress up, ride the public transport, and other routines did before arriving at college. If it turns out that doing those things caused him to be forty minutes late (=40), then his is 30 minutes.

Fortunately, although not in the case of Late Larry, can be a positive or negative constant; for example, a faster-than-usual commute can cause someone to come earlier than she desired. Regardless, it is this that creates a gap between the time an event starts and the time its participant wants to come in the first time.

However, Late Larry is not doomed to come 30 minutes later than when he desires to come as he can adapt and minimize the impact from these obstacles. As he goes to college more often, she starts to dress faster, learn the public transports' timetables, and optimize other routines so that they take less time. This concept is represented in , defined formally as how capable a person is in adapting and correcting the deviation from . In a sense, is a constant that incorporates both willpower and psychological characteristics, examples of which can be read here .

To illustrate the effect of how reduces the time difference between the actual time of arrival and ideal time of arrival, it is raised to the power of . As people only correct things after they have done something wrong, it is appropriate to use instead of just ; in the case of Late Lucy, her first adaptation towards is on her second day of college.

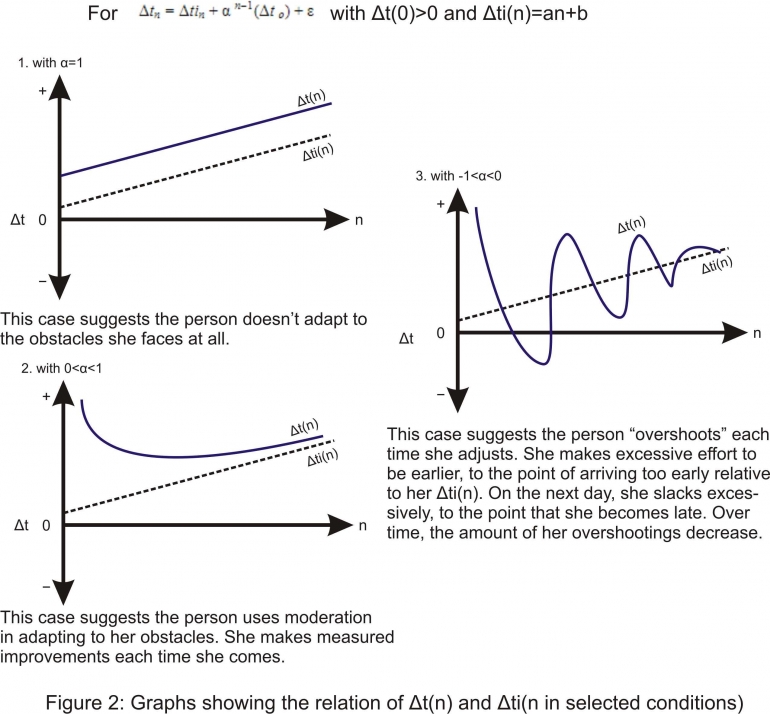

Since it is reasonable to assume that utility-maximizing people tend to try to be late by the amount of their desired difference, then should converge to 0 so that can converge to , as can be seen in Figure 3 below. In order for that to happen, should be a fraction between -1 and 1. It is important to note that it is possible for to be equal to -1 or 1, resulting in a uniform oscillating time path or a divergent line respectively. Regarding the concept of capability, the lower the absolute value of , the more capable the person is of adapting and overcoming the obstacles presented by as it allows for faster convergence.

People's absolute value of can also be lowered by helping them adapt faster to their regular obstacles. Programs such as orientation week, in which one helpful senior passes on information regarding the usual obstacles in coming on time, may help his juniors adapt faster and come on time, or at least on the time they aim to come.

Not that easy, Ferguso

On paper, how tardy a person is should converge to the amount of how tardy he wants to be. In real life, a person's time of arrival may not match the pattern presented above. This difference can be caused by one-off problems, or force majeure, happening on a particular n. Those problems can be caused by factors outside of human control, such as freak weather conditions or falling pianos from the sky, or it can also be caused by factors that to some extent is within human control, such as a broken car.

The common characteristic regarding those factors is that they are exogenous in the equation; although they can change daily, the model can't predict how they change. Such freak occurrences are incorporated in , defined as exogenous residuals to explain the amount of not yet predicted by

Based on the model presented, how late a person comes to a repeating event with an independent schedule is influenced by what time she actually wants to come, how capable she is of going through predictable obstacles, and the unpredictable obstacles falling upon her.

A person may be tardy the first time she participates on a recurring event, yet as she attends the event, again and again, she gets better at overcoming obstacles facing her. However, it doesn't mean that she will come on time in the long term; it is more likely that she will come at the time she desires to arrive.

The takeaway for event organizers seeking to make their audience come on time is that they have to manage expectations. They have to convince that they can reliably deliver utility on time and that their event is worth hurrying to come. If they successfully do that, then there might be a good hope that their participants will come on time.

By Roes Ebara Gikami Lufti | 1706055462 | Staff of Studies Division, Kanopi FEB UI 2018

References (outside hyperlinks):

Sargent, T. Rational Expectations. Retrieved from https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/RationalExpectations.html

Follow Instagram @kompasianacom juga Tiktok @kompasiana biar nggak ketinggalan event seru komunitas dan tips dapat cuan dari Kompasiana. Baca juga cerita inspiratif langsung dari smartphone kamu dengan bergabung di WhatsApp Channel Kompasiana di SINI