1.Theoretical Concept of the Developmental State

Many studies on developmental states generally refer to the experiences of East Asian countries, especially Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan in the 20th century. Chalmers Johnson is considered a pioneer in developmental state studies analyzing Japan's development model and industrial policy. Johnson (1982) used the concept of the developmental state to describe the Japanese government's role in Japan's remarkable and unforeseen post-war economic growth, highlighting the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) as a crucial component of Japan's developmental state.

However, there are studies shows that the developmental state and its associated policies were also evident in the early development histories of industrialized economies like Britain, the United States, France, and Germany (Chang, 2002). At an earlier stage in their histories, they used strategies included active use of subsidies, tariffs, protection for infant industries, and other protective measures like granting monopoly rights. Additionally, these strategies focused on developing national capacities through research, development, education, training, stimulating foreign technology acquisition, and fostering public--private cooperation (Chang, 2008).

Countries in the Latin American region have implemented the developmental state model since the 19th century, although the results are not on par with Japan or South Korea Governments in nations such as Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru intervened in various economic sectors. The main instruments of Latin's government developmental policies included import and export taxes, tariff exemptions, subsidies, subsidized immigration, and low-interest credit (Caldentey, 2009).

In Johnson's (1982) perspective, the developmental state occurs when the government plays a central role in guiding economic development. This role involves not only setting and implementing policies but also actively intervening in the economy to promote industrialization, technological advancement, and economic growth.

There are several characteristics of the developmental state. First, strong government and effective developmental structures. Through strong government, the state can intervene and play an active role in guiding the direction of the national economy in the developmental state model. A strong government must be supported by an effective developmental structure that can carry out its roles optimally. According to Vu (2007), the developmental structures include a stable, centralized government, a cohesive bureaucracy, and effective coercive institutions. Socially, these structures must rely on an alliance with producer classes while excluding workers and peasants. This setup allows a state, if it chooses, to effectively formulate and implement industrialization strategies with minimal concerns about redistribution.

Within a strong government, there is a strong leader who commands the role of government and policies. The source of authority in the developmental state does not align with Weber's "holy trinity" of traditional, rational-legal, and charismatic sources of authority. Instead, it derives from revolutionary authority: the authority of a populace dedicated to transforming their social, political, or economic order (Johnson, 1999). However, in some cases, it cannot be denied that developmental state regimes tend to be authoritarian.

Second, capacity and autonomous bureaucracy. Johnson (1999) emphasized its importance of bureaucrats' capacity. The responsibilities of this bureaucracy is to identify and select the industries to be developed (industrial structure policy). They also determine the best methods for rapidly developing these chosen industries (industrial rationalization policy). Furthermore, they supervise competition in the designated strategic sectors to ensure their economic health and effectiveness. In addition, the state bureaucratic must be autonomous and have enough independence to enforce regulations, guide economic policy, and make strategic decisions without being unduly influenced by private interests (Evans, 1995).

Third, state-business close relationships. Even though the state bureaucracy is autonomous, the state also has close relations with the private sector. Evans (1995) stated that the state must be both embedded and autonomous. For a developmental state to be effective, its bureaucrats must be deeply embedded in networks that connect them with business leaders and other key stakeholders. In the Japanese experience, Johnson (1999) proposed three patterns of state-business interactions including self-control, state control, and public private cooperation.

In all three periods, Oyama Kosuke -- Japanese reviewer, believed there was a consistent pattern of the state cartelizing or compartmentalizing each industry, limiting entry for new players. Consequently, each industry enjoyed a stable, cooperative environment, allowing it to partition the domestic market and export to the American market. This was achieved by endorsing and safeguarding zaibatsu in pre-1945 and keiretsu after 1945 (Johnson, 1999). To a certain extent, this is also the case in the relationship between the government and the chaebols in South Korea. In this relationship, the developmental state model in Korea was state-sponsored loans during Japanese administrative or state-mediated finance in Park Chung Hee era (Cumings, 2005).

Fourth, industrial policy and export-oriented industrialization. Industrial policy is not a replacement for the market. Instead, it is the state's deliberate intervention to modify incentives within markets to influence the behavior of producers, consumers, and investors (Johnson, 1999). Vu (2007), argued that industrial policies including subsidizing inputs, promoting exports, imposing performance standards on industries receiving state support, and creating industrial groups in essential dynamic sectors. Meanwhile, export-oriented industrialization was a basic strategy for economic growth in the developmental state. In South Korea during Park Chung Hee presidency, the government monitored the performance of businesses and rewarded or punished them accordingly (Sangin, 2011). If a firm successfully met its export targets, it received various benefits such as preferential credit and loans, tax exemptions, and subsidies. Furthermore, the Korean government employed all available discretionary measures to promote exports and economic growth.

Fifth, there was a pilot organization established. One of the central elements in the developmental state model is a pilot organization like MITI in Japan's case. The experience of MITI indicates that an agency overseeing industrial policy should incorporate elements of planning, energy, domestic production, international trade, and a portion of financial oversight. MITI's defining features include its compact size, indirect management of government funds, role as a think tank, specialized departments for executing industrial policy at a detailed level, and internal democratic processes (Johnson, 1999).

South Korea followed the Japanese MITI model with the formation of the Economic Planning Board or EPB (Cumings, 2005). The EPB's served as the strategic planning unit. It identified target industries and business sectors, allocating funds and overseeing projects undertaken by both private firms and public enterprises, functioning akin to business divisions within "Korea, Inc." (Sangin, 2011).

Sixth, investment in education and human capital. Japan and Korea are currently known as countries with high quality human resources. Cumings (2005) explained that education has been one of the main concerns of society in Korea for hundreds of years. This long investment and tradition in the field of education has become one of the bases for development in South Korea in the modern era. It is not surprising that South Korea gets advantages from this side by having skilled human resources who can work in sectors needed by many industries. This high quality of human capital also influences the development of research and innovation in various essential economic sectors.

2.Indonesia under the Developmental State Regime

Shortly after independence in 1945, the Indonesian government began to take economic policies and intervene in the economic sector, which can be categorized as a developmental state. Under Sukarno's "The Guided Economy" policy, industrial development was to be accomplished by the state. The plantation industry, which was still managed by Dutch management, was nationalized, and its management was transferred to national bureaucrats. Nationalization policies were also implemented in various sectors, such as oil and gas, banking, and transportation (James, 2000).

However, this initial stage of development was premature due to the weak capacity of the state apparatus in the economic sector and an unprepared developmental structure (Vu, 2007). Eventually, in the mid-1960s, during the final years of Sukarno's leadership, Indonesia faced stagnant economic output, widespread poverty, and hunger, deteriorating infrastructure, and nearly 600 percent hyperinflation due to unchecked deficit financing (Wie, 2012).

After the military regime seized the power 1965, Indonesia started economic development, which were characterized by high degree of state intervention. In pursuing economic goal, the state is not only defining and generating national economic plan but also has a very significant role in its implementation (Winanti, 2002). As Burkett and Landsberg note (2000), Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand were generally perceived as following the Japanese model. Their swift economic growth and industrial transformations seemed to validate the traits of state-led capitalist development. Therefore, this paper aims to explain Indonesia's experience as a developmental state in terms of the six characteristics previously stated. The time frame taken in this article is between 1966-1998, or 32 years during President Suharto's rule in Indonesia, known as the New Order. This period is also known in modern Indonesian history as the era of development. Moreover, Suharto was nicknamed the Father of Indonesia's Development (Bapak Pembangunan).

First, strong government and effective developmental structures. The emergence of Major General Suharto, who played a role in eradicating the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) after the 30 September 1965 uprising, coupled with the worsening economic situation, made most people want a change in President Sukarno's leadership regime. In many studies about Indonesia, at least three main groups supported Suharto's leadership in the early stages: anti-PKI army groups, Islamic groups, and student groups. Hence, since 1966, Indonesia's de facto leader has been Suharto, whose source of authority in Johnson's (1999) perspective is called revolutionary authority: the authority of a population dedicated to transforming their social, political, or economic order.

The New Order government was a highly centralized and one-command government under the control of President Suharto. This regime ruled for over 3 decades with a strong and powerful government. At least three main components were supporting the government at that time, namely the army which had defense and socio-political (dual functions), the bureaucracy with a mono-loyalty character, and the Golkar political party (Aspinall & Fealy, 2010). Through the structure of these three groups, which reached the village level throughout Indonesia, the New Order regime became an effective government. In Vu's (2007) view, the New Order regime had stronger developmental structures and functioned better than the previous regime from an economic point of view.

However, the Indonesian government under Suharto was an authoritarian regime (Crouch, 2010), and one of repressive and coercive regimes in the Third World at the time (Feith, 1982). Indonesia is a typical example of developmental state building under authoritarianism (Sato, 2019). In the first two decades of the New Order, there was the Command for the Restoration of Security and Order (Kopkamtib) institution which became a repressive state coercive tool to create order and stability as the basis for development. The Kopkamtib became a government entity focused on enhancing and maintaining order, security, and stability, with the aim of achieving national stability as a crucial factor for the successful execution of the Five-Year Development Plans specifically, and Long-Term Development more broadly (Tanter, 1991).

Second, capacity and autonomous bureaucracy. In contrast to the capacity of the Old Order bureaucracy during Sukarno's reign, the bureaucrats, especially those who managed the economy at the central government level during the New Order era, had relatively strong capacities. Most of them are Western-trained economists and holds highest position both at the Ministry of Finance (MoF) and the National Development and Planning Agency (Bappenas). Ransom (1970) called them the 'Berkeley mafia' because many of them were graduates of the University of California at Berkeley. Sato (2019) stated, together with the Berkeley Mafia, referred to as the technocrats, there is another essential bureaucratic group that influences development in Indonesia, namely the technologue, they are mostly Western-trained as well. The technologue refers to bureaucrats with expertise in technology and engineering which mainly working at the Ministry of Industry, the State Ministry of Research and Technology, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

The technocrats intervene in macroeconomic policies to create stability, including inflation, interest rates, strategic projects, and debt levels. Meanwhile, the technologist group emphasized the importance of the state-led development of technology-intensive 'strategic industries'. When there were differences of opinion between these two groups, Suharto acted as a balancer and determined which policies needed to be taken. Under Suharto's strong leadership, the state bureaucracy operated relatively autonomously from short-term political interests, including private interests, in determining strategic policy (Sato, 2019).

Third, state-business close relationship. Even though bureaucrats are autonomous from the firm interests, the state also must embed with the private sector for guiding and facilitating the formulation of policies that effectively promote industrial growth and economic development (Evans, 1995). Historically, Suharto itself has been long relationship with the private sector and made fundraising since he was an army commander in the regional level (Jenkins, 2010). Fundraising model and build a tight connection with a selected business key leaders apparently continued during his presidency.

For Indonesia's case, the relationship between state and business seemed even more extreme because Suharto and a handful of businesspeople created patron-client relationships. Anyone who expects access to wealth, projects, and business patronage from the state must be on the president's right side and provide sufficient funds to the president on an "off-budget" basis in exchange for permits, concessions, and privileges (Mackie, 2010). Based on patrimonial relationship, big businesses flourished due to Suharto and government support, through favoring policy, such as subsidy, protection, and special privilege.

Eventually, like the keiretsu in Japan or the chaebols in South Korea, in the New Order era they were also known as crony conglomerates, which referred to the few businessmen, predominantly Chinese, who were in Suharto's inner circle. Most of them still control the economic sector in Indonesia today and are widely known as the Sembilan Naga or Gang of Nine or Nine Dragons (Yesidora, 2023).

Fourth, industrial policy and export-oriented industrialization. Starting in 1969, the government established a Five-year Development Plan (Repelita), which became the basis for medium-term development. These development planning programs are founded on three core principles of development philosophy, known as the "trilogy of development" (Trilogi Pembangunan): equitable wealth distribution, economic growth, and national (political) stability, all aimed at achieving social well-being and justice for the populace (Winanti, 2002). The government also launched an emergency program for recovery and a long-term plan of national development.

According to Sato (2019), the state intervention such as promotion of domestic investment, investment incentives to priority sectors, restriction on foreign ownership and employment, automobile component localization policy, and bonded zone for export production. Meanwhile, deregulation policy including liberalization of foreign exchange control in 1970 and liberalize interest rates in 1983.

For the first 15 years of the New Order era, the government continues to maintain the Import-Substitution Industrialization (ISI) strategy which emphasized fiscal policy to reduce import and provide a favorable circumstance for the promotion of domestic industry (Wie, 2012). However, after the oil boom ended in the 1980s, the government switched to an Export-Oriented Industrialization (EOI) policy, seeing the success of South Korea and Taiwan and the various weaknesses in ISI policy (Djidin, 2007). From inward-looking to outward-looking strategy. This change in strategy also accelerated industrialization in Indonesia, leading to a transformation of the economic structure from agriculture to industry. The employment share of the agricultural sector steadily declined, while the shares of the manufacturing and services sectors increased simultaneously as shown in Figure 1. Since then, the manufacturing sector has become the driving force of economic growth (Puspitawati, 2021).

Fifth, the existence a pilot organization. Like South Korea with its the EPB, Indonesia have Bappenas as a pilot organization, which had a very crucial role in designing, defining, and formulating of Repelita, and led by the technocrats. Bappenas policies created a protective framework that facilitated the emergence of domestic capital, primarily dominated by state corporations, military-owned companies, and their domestic Chinese corporate clients (Robison, 1986). However, since the power centralized in Suharto's hand, Bappenas does not have enough effective power to ensure that the planning and development implementation process is carried out in accordance with the principles of merit system and good governance. Bappenas cannot fully act like Korea's EPB which can control and punish the businesses (Putra, 2024).

Sixth, investment in education and human capital. Through the restoration of monetary stability and the rehabilitation of the deteriorated productive apparatus and infrastructure, the Indonesian economy experienced unprecedented rapid and sustained growth in the New Order era (Wie, 2007). According to the World Bank (2023), Indonesia's GDP growth in 1965 was only around 1.1%. In the first two years of the New Order, economic growth reached double digits in 1968, at 10.9%, and again double digits in 1980, at 10%. After the oil boom was over in 1985, economic performance corrected to 2.5% and rose again to 7.8% in 1996 before falling due to the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1999.

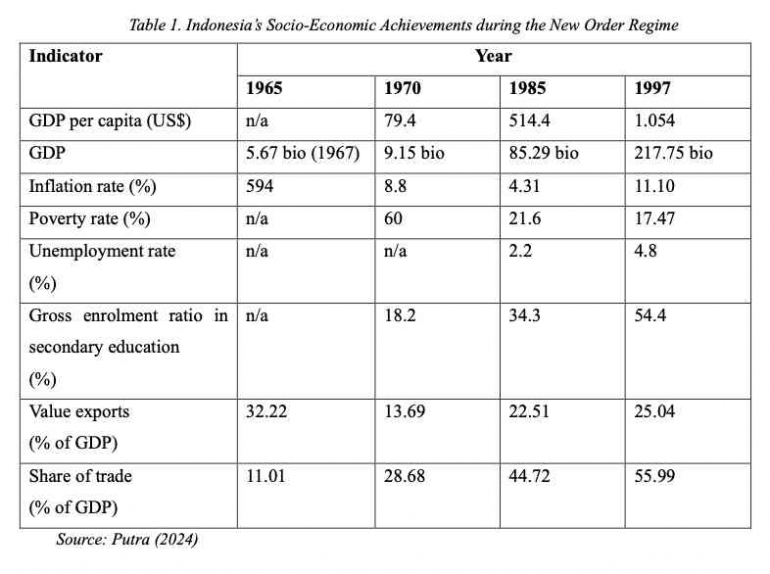

As shown in Table. 1, the increase in economic performance is accompanied by increases in other achievements, such as improving levels of education. The technocrats at Bappenas were also highly conscious of the importance of social development. They created phenomenal programs that is still impactful today, namely program of Sekolah Inpres (one elementary school in each village) and program of one Puskesmas (public health center) in each district (Sato, 2019). Those human capital investment programs are essential foundations in the development and transformation of a nation.However, behind the impressive achievements of the New Order, there is a critical question: why was Indonesia unable to transform into a developed country like South Korea or Japan after the developmental state of 1966-1998? The reasoning is there are several weaknesses of the New Order development regime that hampered transformation. First, there is a severe level of corruption and involvement of the president's family in state-sponsored business (Winanti, 2002). Suharto's family members were given every conceivable advantage in establishing their business empires. This included monopoly control over certain spices, like cloves, and various domestic industries, such as citrus fruit. The Suharto children gained increasing prominence by securing government contracts for projects like toll roads, power initiatives, and the poorly conceived "national car" program (James, 2000).

Second, Bappenas as a bureaucratic motor in development, does not have full authority and solid political support like the Korean EPB. For instance, it difficult for state-supported business groups to be punished when they made mistakes because they enjoyed high privileges if they were good clients of Suharto as their patron. This weak coordinating institution means that the state bureaucracy is not effective enough to create miraculous achievements like in South Korea (Putra, 2024).

Third, the government was unable to integrate and implement EOI's long-term industrial policy. According to Djidin (2007), the EOI's policy in Indonesia often focus on low-value-added manufacturing with minimal technology transfer and innovation, and emphasis on exporting raw materials or semi-processed goods. This hampers the development of a robust and diverse industrial base. Furthermore, the Indonesia's EOI often depends heavily on foreign direct investment (FDI), led to economic dependence on foreign investors and the repatriation of profits out of the country.

3.Conclusion

Indonesia experienced a developmental state during the New Order regime from 1966 to 1998, which was measured based on six characteristics. The New Order government was a model of centralistic and unified command under Suharto's administration. This regime was supported by an effective developmental structure through three main groups: the military, the bureaucracy, and the Golkar Party. In addition, to create order and stability in development, the first 20 years of the New Order saw the establishment of Kopkamtib as a repressive and coercive state instrument. The strength of this regime was also supported by a relatively better and more autonomous bureaucracy compared to the Old Order government, with the presence of two main groups of bureaucrats in development matters: the technocrats and the technologue.

Meanwhile, the relationship between the government and businesses was also very close, especially with the conglomerates who were Suharto's clients. They received privileges, protection, and support from the state within the framework of industrial policy. Furthermore, the shift in policy paradigm from ISI to EOI after the end of the oil boom in the 1980s had a positive impact on Indonesia's economic achievements. This progress was accompanied by increased government social investment in education, human resources, and health sectors, the effects of which can still be felt today. These achievements cannot be separated from the role of the pilot organization, Bappenas, which functions in designing and formulating development plans, despite in some extent by political factor, this organization did not have enough power and less effective to control the implementation.

However, even though the New Order's achievements are remarkable, Indonesia's accomplishments are not as miraculous as those of South Korea or Japan due to several weaknesses, such as high levels of corruption, ineffective pilot organizations, and imperfect implementation of EOI policies.

* The original article was submitted as a final assignment for the Development Policies in the Global Context class at the Graduate School of Public Administration, Seoul National University, in Spring Semester 2024

Reference

Aspinall, E., & Fealy, G. (2010). Soeharto's New Order Legacy: Essays in honour of Harold Crouch. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Burkett, P., & Landsberg, H. M. (2000). Development, Crisis, and Class Struggle: Learning from Japan and East Asia. London: McMillan Press.

Caldentey, E. P. (2009). The Concept and Evolution of the Developmental State. International Journal of Political Economy, 37(3), 27-53.

Chang, H.-J. (2002). Kicking Away the Ladder: Developmental Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem Press.

Chang, H.-J. (2008). Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Crouch, H. (2010). Political Reform in Indonesia after Soeharto. Singapore: ISEAS.

Cumings, B. (2005). State Building in Korea: Continuity and Crisis. In M. Lange, & D. Rueschmeyer, States and Development: Historical Antecedents of Stagnation and Advance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Djidin, D. A. (2007). The Political Economy of Indonesia's New Economic Policy. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 27(1), 14-36.

Evans, P. (1995). Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Feith, H. (1982, Spring). Repressive-Development Regimes in Asia. Alternatives, 7(4), 491-506.

James, W. E. (2000). Lessons from Development of the Indonesian Economy. Education About Asia, 5(1), pp. 31-36.

Jenkins, D. (2010). One Reasonably Capable Man: Soeharto's Early Fundraising. In E. Aspinall, & G. Fealy, Soeharto's New Order Legacy: Essays in honour of Harold Crouch. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Johnson, C. (1982). MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy 1925-1975. Redwood: Standford University Press.

Johnson, C. (1999). The Developmental State: Odyssey of a Concept. In M. Woo-Cumings, The Developmental State. Itacha: Cornell University Press.

Mackie, J. (2010). Patrimonialism: The New Order and Beyond. In E. Aspinall, & G. Fealy, Soeharto's New Order Legacy: Essays in honour of Harold Crouch. Canberra: ANU E Press.

Puspitawati, E. (2021). Indonesian Industrialization and Industrial Policy: Peer Learning from China's Experiences. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. United Nations.

Putra, E. A. (2024, March 13). Why Indonesia Missing to Achieve a Miracle?: A Comparative Study Indonesia-South Korea Economic Development during Indonesia's New Order Regime. Retrieved May 2024, from www.kompasiana.com: https://www.kompasiana.com/ekamara/65f1a094c57afb4c6c786352/why-indonesia-missing-to-achieve-a-miracle-a-comparative-study-indonesia-south-korea-economic-development-during-indonesia-s-new-order-regime

Ransom, D. (1970, October). The Berkeley Mafia and the Indonesian Masssacre. Rampants, 9(4), 40-49.

Robison, R. (1986). Indonesia: The Rise of Capital. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Sangin, P. (2011). Government Roles in Korea's Economic Development from a Perspective of the Institutions Hypothesis. The Korean Journal of Policy Studies, 26(3), 115-128.

Sato, Y. (2019). Reemerging Developmental State in Democratized Indonesia. In Y. Takagi, V. Kanchoocat, & T. Sonobe, Developmental State Building: The Politics of Emerging Economies. Singapore: Springer.

Tanter, R. (1991). Intelligence Agencies and Third World Militarization: A Case Study of Indonesia, 1966-1989. Thesis (PhD). Monash University.

Vu, T. (2007). State Formation and the Origins of Developmental States in South Korea and Indonesia. Studies in Comparative International Development, 41(4), 27-56.

Wie, T. K. (2007). Indonesia's Economic Performance under Soeharto's New Order Regime. Seoul of Journal Economics, 20(2), 263-281.

Wie, T. K. (2012). Indonesia's Economy since Independence. Singapore: ISEAS.

Winanti, P. (2002). A Comparative Political Economy of Development of Korea and Indonesia: Historical-Structuralist Explanation. Thesis (Master). KDI School of Public Policy and Managament.

World Bank. (2023). GDP growth (annual %) - Indonesia. Retrieved May 2024, from www.data.worldbank.org: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=ID

Yesidora, A. (2023, July 21). Legenda Sembilan Naga, Kelompok Pengusaha Berjaya di Era Orde Baru [The Legend of the Nine Dragons, a Successful Entrepreneurial Group in the New Order Era]. Retrieved May 2024, from www.katadata.co.id: https://katadata.co.id/ekonopedia/sejarah-ekonomi/6492e103e2a5e/legenda-sembilan-naga-kelompok-pengusaha-berjaya-di-era-orde-baru

Baca konten-konten menarik Kompasiana langsung dari smartphone kamu. Follow channel WhatsApp Kompasiana sekarang di sini: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaYjYaL4Spk7WflFYJ2H