Welcome Learners!

As the world comes together in response to the Coronavirus pandemic and to mitigate the spread of the virus, learners are needing to navigate new ways of meeting their educations goals. I am offering this free course to help learners prepare for remote and online learning. This course is designed to empower you to get the most out of your online learning experience, no matter where your learning takes place.

The series of modules introduce you to foundational strategies and techniques to help you reach your learning goals. We talk about the importance of self-care and sleep, addressing challenges involved with creating a space for learning, time management, effective study strategies and practices, and social learning.

Lets get started.

GETTING STARTED

Welcome to this short book of "How to Learn Online". During this difficult time when millions of us around the world are caring for our communities by social distancing and working and learning from home, this book is created to help achieve your learning goals. You may find that learning online is more flexible than learning in face-to-face environments. Often in online course, you can move at your own pace, reviewing material that is difficult or skipping things you have already mastered.

Online learning environments can also increase opportunities can also increase opportunities to connect with your peers and instructor through synchronous video conferencing and asynchronous discussion forums. To be a successful online learner requires commitment and planning. But don't be daunted. This brief book will help you prepare for learning online, giving you practical advice and strategies informed by the science learning.

Learning online is NOT about learning alone. In fact, social learning (learning with others) is an important aspects of successful learning.

WHAT IS SELF-CARE?

Self-Care for Learning

One observation that I would say is universally true is that self -- care is critical for successful learning. A healthy mind and body is a mind ready to learn. Self-care means taking an active role in preserving and protecting your well-being and it is especially important during times of stress and change.

What is self-care? Self-care is any activity or practice done deliberately to nurture your emotional, mental, and physical health. While self-care is rather broad topic, in this module we will highlight self-care techniques that support your ability to learn.

STRESS AND LEARNING

You might be wondering why at the beginning this book on learning with the topic of self-care and stress management. Stress can have a significant impact on learning, particularly on memory. While stress can improve attention and alertness and thus help with memory formation (encoding), too much stress can impair our cognitive function by negatively impacting our brain's ability to retrieve information or update existing information. Retrieval information is critical during exams of course, but is also important when we need to recall and put into action newly acquired skills. Our ability to update information is important when learning complex concepts that build or change over time. Learning to manage stress in turns helps our brain to learn.

A QUICK PAUSE TO BREATHE

Before we continue, let's pause here for a very basic technique to help you get grounded -- belly breathing, also referred to as diaphragmatic breathing. At any point you need to calm and refocus your thoughts and emotions, practicing this breathing exercise will help settle and centre you mind.

Make note of how you feel at this moment; jot down a few words. Practice the technique below a few times and then make a note of how you feel after. What differences are you noticing? Did you find this helpful?

Belly Breathing steps:

- Lay down or sit comfortably

- Put one hand on you belly just below your ribs and place your other hand on your chest.

- Take a deep breath in through your nostrils, letting your belly push your hand out. Try to do this without raising your chest.

- Breathe out through slightly parted lips, and feel your belly hand drop. Use your hand to gently push the air out.

- Repeat for 3 to 10 cycles, taking at least 10 second for each breath.

What other techniques do you use for managing stress?

THE ROLE OF MEMORY LEARNING

Learning and memory are two sides of the same coin. Learning refers to the process of acquiring new skill or knowledge. Memory is the expression of what you have learned. For example, consider the effort it takes for a child to learn how tie their shoe. They need to watch the movement and listen to instruction from someone who knows hot tie a shoe.

The child must also practice many times, going through each step, feeling the movement of the laces and coordinations of their fingers. This effort is learning. Eventually, the child can recall the steps without being shown or told, and finally tie their shoe quickly from memory.

And when you forget something, you have to relearn it, encoding the skill or knowledge again to memory.

Throughout this book we will reference the role of memory to learning, and in the additional resources I have listed several sources for further understanding how memory and leaning works.

SLEEP AND MEMORY

Later in this book you will discover memory techniques to improve the effectiveness of your learning. But, you likely already practice an important skill for learning everyday -- sleep!!!

An active and awake brain is necessary for encoding new memories, such as learning new concepts and skills. But during sleep our brains is also actively consolidating our memories.

According to the book, learning and memory: a comprehensive reference, memory consolidation is the process by which recently learned experiences are transformed into long-term memory. During sleep, our brain takes advantage of less awake-time activity to make the structural and chemical changes in the nervous system needed for long-term memory.

What is you sleep number?

While everyone's sleep number -- the hours of sleep you need each night can vary, according to the US National Sleep Foundation, adults between the ages of 18 and 64 should get between 7 and 9 hours of uninterrupted sleep. The sleep Foundation offers tips for healthy sleeping, and you may also consider keeping a sleep diary to track your sleep and find ways you can improve your sleep.

- Keep regular bedtimes and wake up time, even on the weekends.

- Plan time to wind down before bedtime. Minimize exposure to blue light from devices like your phone or your laptop.

- You sleep environmental should be cool, free form disturbing noises, and any light. You might want to use things like blackout curtains, an eye mask, ear plugs, and white noise machine (or another appliance like a fan or humidifier to mask noise).

- Avoid alcohol, cigarettes, caffeine, and heavy meals in the evening.

- Anything related to work and entertainment (computers, TVs, etc) should be removed from the bedroom.

Healthy sleep tips

It's well-established that sleep is essential to our physical and mental health. But despite its importance, a troubling percentage of people find themselves regularly deprived of quality sleep and are notably sleepy during the day.

Though there's a wide range of causes and types of sleeping problems, expert consensus points to ha handful of concreate steps that promote mora restful sleep. Organizations like CDC, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute on Aging, and the American Academy of family Physicians point to the same fundamental tips for getting better rest.

For many people, trying to implement all these strategies can be overwhelming. But remember that it's not all-or-thing; you can start with small changes and work your way up toward healthier sleep habits, also known as sleep hygiene

To make these hygiene improvements more approachable, we've broken them into four categories:

- Creating s Sleep-Inducing Bedroom

- Optimizing your sleep schedule

- Crafting a pre-bed time routine

- Fostering pro-sleep habits during the day

In each category, you can find specific actions that you can take to make it easier to fall asleep , stay asleep, and wake up well-rested.

CREATING A SLEEP-INDUCING BEDROOM

An essential tip to help fall asleep quickly and easily is to make sure your bedroom a place of comfort and relaxation. Though this might seem obvious, it's often overlooked, contributing to difficulties getting to sleep and sleeping through the night.

In designing your sleep environment, focus maximizing comfort and minimizing distractions, including these tips:

- Use a high-performance mattress and pillow: a quality mattress is vital to making sure that you are comfortable enough to relax. It also endures, along with your pillow, that you spine gets proper support to avoid aches and pains.

- Choose quality bedding: your sheets and blankets play a major role in helping your bed feel inviting. Look for bedding that feels comfortable to the touch and that will help maintain a comfortable temperature during the night.

- Avoid light disruption: excess light exposure can throw off your sleep and circadian rhythm. Blackout curtains over your windows or a sleep mask for over your eyes can block light and prevent it from interfering with your rest.

- Cultivate peace and quiet: keeping noise to a minimum is an important part of building a sleep-positive bedroom. If you can't eliminate nearby sources of noise, consider drowning them out with a fan or white noise white machine. Earplugs or headphones are another option to stop abrasive sounds from bothering you when you want to sleep.

- Find an agreeable temperature: you don't want your bedroom temperature to be a distraction by feeling too hot or too cold. The ideal temperature can vary based on the individual, but most research support sleeping in a cooler room that is around 65 degrees.

- Introduce pleasant aromas: alight scent that you can find calming can help ease you into sleep. Essential oils with natural aromas such as lavender, can provide a soothing and fresh smell for your bedroom.

OPTIMIZING YOUR SLEEP SCHEDULE

Taking control of your daily sleep schedule is a powerful step toward getting a better sleep. To start harnessing your schedule for your benefit, try implementing these four strategies:

Set a Fixed Wake-Up Time: It's close to impossible for your body to get accustomed to a healthy sleep routine if you're constantly waking up at different times. Pick a wake-up time and stick with it, even on weekends or other days when you would otherwise be tempted to sleep in.

Budget Time for Sleep: If you want to make sure that you're getting the recommended amount of sleep each night, then you need to build that time into your schedule. Considering your fixed wake-up time, work backwards and identify a target bedtime. Whenever possible, give yourself extra time before bed to wind down and get ready for sleep.

Be Careful With Naps: To sleep better at night, it's important to use caution with naps. If you nap for too long or too late in the day, it can throw off your sleep schedule and make it harder to get to sleep when you want to. The best time to nap is shortly after lunch in the early afternoon, and the best nap length is around 20 minutes.

Adjust Your Schedule Gradually: When you need to change your sleep schedule, it's best to make adjustments little-by-little and over time with a maximum difference of 1-2 hours per night6. This allows your body to get used to the changes so that following your new schedule is more sustainable.

Crafting a Pre-Bed Routine

If you have a hard time falling asleep, it's natural to think that the problem starts when you lie down in bed. In reality, though, the lead-up to bedtime plays a crucial role in preparing you to fall asleep quickly and effortlessly.

Poor pre-bed habits are a major contributor to insomnia and other sleep problems. Changing these habits can take time, but the effort can pay off by making you more relaxed and ready to fall asleep when bedtime rolls around.

As much as possible, try to create a consistent routine that you follow each night because this helps reinforce healthy habits and signals to mind and body that bedtime is approaching. As part of that routine, incorporate these three tips:

Wind Down For At Least 30 Minutes: It's much easier to doze off smoothly if you are at-ease. Quiet reading, low-impact stretching, listening to soothing music, and relaxation exercises are examples of ways to get into the right frame of mind for sleep.

Lower the Lights: Avoiding bright light can help you transition to bedtime and contribute to your body's production of melatonin, a hormone that promotes sleep.

Disconnect From Devices: Tablets, cell phones, and laptops can keep your brain wired, making it hard to truly wind down. The light from these devices can also suppress your natural production of melatonin. As much as possible, try to disconnect for 30 minutes or more before going to bed.

Fostering Pro-Sleep Habits During the Day

Setting the table for high-quality sleep is an all-day affair. A handful of steps that you can take during the day can pave the way for better sleep at night.

See the Light of Day: Our internal clocks8 are regulated by light exposure. Sunlight has the strongest effect, so try to take in daylight by getting outside or opening up windows or blinds to natural light. Getting a dose of daylight early in the day can help normalize your circadian rhythm. If natural light isn't an option, you can talk with your doctor about using a light therapy box.

Find Time to Move: Daily exercise has across-the-board benefits for health, and the changes it initiates in energy use and body temperature can promote solid sleep. Most experts advise against intense exercise close to bedtime because it may hinder your body's ability to effectively settle down before sleep.

Monitor Your Caffeine Intake: Caffeinated drinks, including coffee, tea, and sodas, are among the most popular beverages in the world. Some people are tempted to use the jolt of energy from caffeine to try to overcome daytime sleepiness, but that approach isn't sustainable and can cause long-term sleep deprivation. To avoid this, keep an eye on your caffeine intake and avoid it later in the day when it can be a barrier to falling sleep.

Be Mindful of Alcohol: Alcohol can induce drowsiness, so some people are keen on a nightcap before bed. Unfortunately, alcohol affects the brain in ways that can lower sleep quality, and for that reason, it's best to avoid alcohol in the lead-up to bedtime.

Don't Eat Too Late: It can be harder to fall asleep if your body is still digesting a big dinner. To keep food-based sleep disruptions to a minimum, try to avoid late dinners and minimize especially fatty or spicy foods. If you need an evening snack, opt for something light and healthy.

Don't Smoke: Exposure to smoke, including secondhand smoke, has been associated with a range of sleeping problems including difficulty falling asleep and fragmented sleep.

Reserve Your Bed for Sleep and Sex Only: If you have a comfortable bed, you may be tempted to hang out there while doing all kinds of activities, but this can actually cause problems at bedtime. You want a strong mental association between your bed and sleep, so try to keep activities in your bed limited strictly to sleep and sex.

If You Can't Fall Asleep

Whether it's when you first get into bed or after waking up in the middle of the night, you may find it hard to drift off to sleep. These tips help explain what to do when you can't sleep:

Try Relaxation Techniques: Don't focus on trying to fall asleep; instead, focus on just trying to relax. Controlled breathing, mindfulness meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery are examples of relaxation methods that can help ease you into sleep.

Don't Stew in Bed: You want to avoid a connection in your mind between your bed and frustration from sleeplessness. This means that if you've spent around 20 minutes in bed without being able to fall asleep, get out of bed and do something relaxing in low light. Avoid checking the time during this time. Try to get your mind off of sleep for at least a few minutes before returning to bed.

Experiment With Different Methods: Sleeping problems can be complex and what works for one person may not work for someone else. As a result, it makes sense to try different approaches to see what works for you. Just remember that it can take some time for new methods to take effect, so give your changes time to kick in before assuming that they aren't working for you.

Keep a Sleep Diary: A daily sleep journal can help you keep track of how well you're sleeping and identify factors that might be helping or hurting your sleep. If you're testing out a new sleep schedule or other sleep hygiene changes, the sleep diary can help document how well it's working.

Talk With a Doctor: A doctor is in the best position to offer detailed advice for people with serious difficulties sleeping. Talk with your doctor if you find that your sleep problems are worsening, persisting over the long-term, affecting your health and safety (such as from excessive daytime sleepiness), or if they occur alongside other unexplained health problems.

TAKE A SHORT NAP

If your energy and ability start to wane. Why not take a nap? Much like sleep, brief napsot only aid with memory consolidation, but can also be restorative. Sleep research has demonstrated that cognitive function - critical for learning - is improved after a nap. Napping also helps with problem solving, short-term memory, and alertness.

The ideal nap time is 10 to 20 minutes. Anything less than 10 minutes does not provide the restorative effects to your brain, and longer than 25 minutes can make you feel drowsy and cloud your ability to think clearly.

In his book When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing, author Daniel Pink offers a 5-step guide to taking a "nappuccino" which involves drinking a small cup of coffee before settling down for a 20 minute nap.

Healthy routine

In order for you to be fully available to your family, friends and coworkers, you need to put your well-being first. This means maintaining healthy habits like getting enough sleep, staying hydrated and eating well, getting regular physical exercise, and taking breaks. You might explore wellness apps that can help you create and manage healthy habits.

It can be difficult to give ourselves the timeout we need as the pace and demands of the day push us forward. To help you take a moment for yourself, consider scheduling your breaks. Later in this course we will cover time management strategies and setting a study schedule. Add breaks directly to your study schedule and honor that time as you would an appointment with a doctor or meeting with a friend.

Ideas for Quick Breaks

- Sunlight and fresh air. This can go hand-in-hand with getting some exercise or walking your dog.

- Meditation, yoga, and breathing exercises.

- Connecting with friends and family.

What do you do for a quick break?

Checklist for Managing Self-Care

HOW MEMORY WORKS

Memory is the ongoing process of information retention over time. Because it makes up the very framework through which we make sense of and take action within the present, its importance goes without saying. But how exactly does it work? And how can teachers apply a better understanding of its inner workings to their own teaching? In light of current research in cognitive science, the very, very short answer to these questions is that memory operates according to a "dual-process," where more unconscious, more routine thought processes (known as "System 1") interact with more conscious, more problem-based thought processes (known as "System 2"). At each of these two levels, in turn, there are the processes through which we "get information in" (encoding), how we hold on to it (storage), and and how we "get it back out" (retrieval or recall). With a basic understanding of how these elements of memory work together, teachers can maximize student learning by knowing how much new information to introduce, when to introduce it, and how to sequence assignments that will both reinforce the retention of facts (System 1) and build toward critical, creative thinking (System 2).

Dual-Process Theory

Think back to a time when you learned a new skill, such as driving a car, riding a bicycle, or reading. When you first learned this skill, performing it was an active process in which you analyzed and were acutely aware of every movement you made. Part of this analytical process also meant that you thought carefully about why you were doing what you were doing, to understand how these individual steps fit together as a comprehensive whole. However, as your ability improved, performing the skill stopped being a cognitively-demanding process, instead becoming more intuitive. As you continue to master the skill, you can perform other, at times more intellectually-demanding, tasks simultaneously. Due to your knowledge of this skill or process being unconscious, you could, for example, solve an unrelated complex problem or make an analytical decision while completing it.

In its simplest form, the scenario above is an example of what psychologists call dual-process theory. The term "dual-process" refers to the idea that some behaviors and cognitive processes (such as decision-making) are the products of two distinct cognitive processes, often called System 1 and System 2 (Kaufmann, 2011:443-445). While System 1 is characterized by automatic, unconscious thought, System 2 is characterized by effortful, analytical, intentional thought (Osman, 2004:989).

Figure 1: A summary of System 1 and System 2. (Source: Upfront Analytics, 2015)

Dual-Process Theories and Learning

How do System 1 and System 2 thinking relate to teaching and learning? In an educational context, System 1 is associated with memorization and recall of information, while System 2 describes more analytical or critical thinking. Memory and recall, as a part of System 1 cognition, are focused on in the rest of these notes.

As mentioned above, System 1 is characterized by its fast, unconscious recall of previously-memorized information. Classroom activities that would draw heavily on System 1 include memorized multiplication tables, as well as multiple-choice exam questions that only need exact regurgitation from a source such as a textbook. These kinds of tasks do not require students to actively analyze what is being asked of them beyond reiterating memorized material. System 2 thinking becomes necessary when students are presented with activities and assignments that require them to provide a novel solution to a problem, engage in critical thinking, or apply a concept outside of the domain in which it was originally presented.

It may be tempting to think of learning beyond the primary school level as being all about System 2, all the time. However, it's important to keep in mind that successful System 2 thinking depends on a lot of System 1 thinking to operate. In other words, critical thinking requires a lot of memorized knowledge and intuitive, automatic judgments to be performed quickly and accurately.

How does Memory Work?

In its simplest form, memory refers to the continued process of information retention over time. It is an integral part of human cognition, since it allows individuals to recall and draw upon past events to frame their understanding of and behavior within the present. Memory also gives individuals a framework through which to make sense of the present and future. As such, memory plays a crucial role in teaching and learning. There are three main processes that characterize how memory works. These processes are encoding, storage, and retrieval (or recall).

- Encoding. Encoding refers to the process through which information is learned. That is, how information is taken in, understood, and altered to better support storage (which you will look at in Section 3.1.2). Information is usually encoded through one (or more) of four methods: (1) Visual encoding (how something looks); (2) acoustic encoding (how something sounds); (3) semantic encoding (what something means); and (4) tactile encoding (how something feels). While information typically enters the memory system through one of these modes, the form in which this information is stored may differ from its original, encoded form (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014).

- Storage. Storage refers to how, where, how much, and how long encoded information is retained within the memory system. The modal model of memory (storage) highlights the existence of two types of memory: short-term and long-term memory. Encoded information is first stored in short-term memory and then, if need be, is stored in long-term memory (Roediger & McDermott, 1995). Atkinson and Shiffrin argue that information that is encoded acoustically is primarily stored in short-term memory (STM), and it is only kept there through constant repetition (rehearsal). Time and inattention may cause information stored in STM to be forgotten. This is because short-term memory only lasts between 15 and 30 seconds. Additionally, STM only stores between five and nine items of information, with seven items being the average number. In this context, the term "items" refers to any piece of information. Long-term memory, however, has immense storage capacity, and information stored within LTM can be stored there indefinitely. Information that is encoded semantically is primarily stored in LTM; however, LTM also stores visually- and acoustically-encoded information. Once information is stored within LTM or STM, individuals need to recall or retrieve it to make use of said information (Roediger & McDermott, 1995). It is this retrieval process that often determines how well students perform on assignments designed to test recall.

Figure 2: The differences between STM and LTM. (Adapted from: Roediger & McDermott, 1995)

- Retrieval. As indicated above, retrieval is the process through which individuals access stored information. Due to their differences, information stored in STM and LTM are retrieved differently. While STM is retrieved in the order in which it is stored (for example, a sequential list of numbers), LTM is retrieved through association (for example, remembering where you parked your car by returning to the entrance through which you accessed a shopping mall) (Roediger & McDermott, 1995).

Improving Recall

Retrieval is subject to error, because it can reflect a reconstruction of memory. This reconstruction becomes necessary when stored information is lost over time due to decayed retention. In 1885, Hermann Ebbinghaus conducted an experiment in which he tested how well individuals remembered a list of nonsense syllables over increasingly longer periods of time. Using the results of his experiment, he created what is now known as the "Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve" (Schaefer, 2015).

Figure 3: The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve. (Source: Schaefer, 2015)

Through his research, Ebbinghaus concluded that the rate at which your memory (of recently learned information) decays depends both on the time that has elapsed following your learning experience as well as how strong your memory is. Some degree of memory decay is inevitable, so, as an educator, how do you reduce the scope of this memory loss? The following sections answer this question by looking at how to improve recall within a learning environment, through various teaching and learning techniques.

As a teacher, it is important to be aware of techniques that you can use to promote better retention and recall among your students. Three such techniques are the testing effect, spacing, and interleaving.

- The testing effect. In most traditional educational settings, tests are normally considered to be a method of periodic but infrequent assessment that can help a teacher understand how well their students have learned the material at hand. However, modern research in psychology suggests that frequent, small tests are also one of the best ways to learn in the first place. The testing effect refers to the process of actively and frequently testing memory retention when learning new information. By encouraging students to regularly recall information they have recently learned, you are helping them to retain that information in long-term memory, which they can draw upon at a later stage of the learning experience (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014). As secondary benefits, frequent testing allows both the teacher and the student to keep track of what a student has learned about a topic, and what they need to revise for retention purposes. Frequent testing can occur at any point in the learning process. For example, at the end of a lecture or seminar, you could give your students a brief, low-stakes quiz or free-response question asking them to remember what they learned that day, or the day before. This kind of quiz will not just tell you what your students are retaining, but will help them remember more than they would have otherwise.

- Spacing. According to the spacing effect, when a student repeatedly learns and recalls information over a prolonged time span, they are more likely to retain that information. This is compared to learning (and attempting to retain) information in a short time span (for example, studying the day before an exam). As a teacher, you can foster this approach to studying in your students by structuring your learning experiences in the same way. For example, instead of introducing a new topic and its related concepts to students in one go, you can cover the topic in segments over multiple lessons (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014).

- Interleaving. The interleaving technique is another teaching and learning approach that was introduced as an alternative to a technique known as "blocking". Blocking refers to when a student practices one skill or one topic at a time. Interleaving, on the other hand, is when students practice multiple related skills in the same session. This technique has proven to be more successful than the traditional blocking technique in various fields (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014).

As useful as it is to know which techniques you can use, as a teacher, to improve student recall of information, it is also crucial for students to be aware of techniques they can use to improve their own recall. This section looks at four of these techniques: state-dependent memory, schemas, chunking, and deliberate practice.

- State-dependent memory. State-dependent memory refers to the idea that being in the same state in which you first learned information enables you to better remember said information. In this instance, "state" refers to an individual's surroundings, as well as their mental and physical state at the time of learning (Weissenborn & Duka, 2000).

- Schemas. Schemas refer to the mental frameworks an individual creates to help them understand and organize new information. Schemas act as a cognitive "shortcut" in that they allow individuals to interpret new information quicker than when not using schemas. However, schemas may also prevent individuals from learning pertinent information that falls outside the scope of the schema that has been created. It is because of this that students should be encouraged to alter or reanalyze their schemas, when necessary, when they learn important information that may not confirm or align with their existing beliefs and conceptions of a topic.

- Chunking. Chunking is the process of grouping pieces of information together to better facilitate retention. Instead of recalling each piece individually, individuals recall the entire group, and then can retrieve each item from that group more easily (Gobet et al., 2001).

- Deliberate practice. The final technique that students can use to improve recall is deliberate practice. Simply put, deliberate practice refers to the act of deliberately and actively practicing a skill with the intention of improving understanding of and performance in said skill. By encouraging students to practice a skill continually and deliberately (for example, writing a well-structured essay), you will ensure better retention of that skill (Brown et al., 2014).

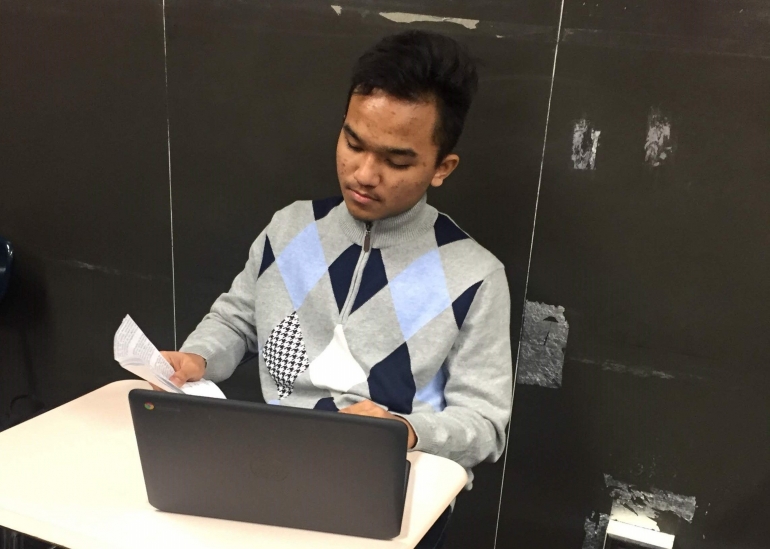

Location, Location, Location

Try to find a location for learning that is as free from distractions as you can manage. In your home, identify a distinct space for learning that is not used for other activities, such as sleeping or watching television. As best you can, the space should be for study only. In small living spaces or where you may share space with family members or roommates, this can be difficult. If your choices are limited and you must set up your learning space in a common area, such as a kitchen, try to arrange a schedule with others so that you are able to use the space uninterrupted during your learning time.

When you are learning, keep water handy to stay hydrated, have healthy snacks nearby, and be sure to get up to stretch as often as you need. Work in an area that has good lighting. If you are working on a computer or tablet, give your eyes a break. Use the 20-20-20 rule: Every 20 minutes, take a 20-second break and focus your eyes on something at least 20 feet away.

Minimize distractions in both your physical environment and your digital environment. Close web browser windows not relevant to your learning, turn off notifications from your phone such as email and social media, and keep the TV off.

- Create your learning space. Identify a distinct space for learning. Avoid areas used for sleeping or common, high-traffic areas.

- Take regular breaks. Stand up to stretch. Rest your eyes every 20 minutes.

- Minimize distractions. Close browser tabs and windows not relevant to your learning. Turn off all phone notifications.

Logistics Checklist

Creating a Schedule

A benefit of online learning is flexibility, but that can also create challenges. Without the structure of an on campus course schedule or in person learning sessions, it can be easy to procrastinate learning tasks or lose track of assignment deadlines. When we are learning while also working and caring for family members, we often deprioritize our learner goals in the face of other demands.

To help you stay on track, find ways to structure and optimize your time for when you learn best. This might mean waking up an hour earlier than usual, before children are awake, in order to complete reading and video lectures. Or, you may need to save the latest episode of your favorite television show for another evening, as you finish an important project or study for an upcoming exam.

Review the learning activities and determine how much time you expect each will take, then make a plan that works for you. You might be tempted to "binge learn" and move through course materials too quickly. Pace yourself. When you set aside time for learning, this doesn't necessarily mean you need to find four-hour uninterrupted blocks, several days a week. You may find 15 minutes to watch a short video lecture and write a three-sentence reflection post. But of course, other learning activities will require more time. In fact, it's a good rule of thumb to overestimate the amount of time you expect to take for a task and factor that into your schedule.

Create a schedule for your work, especially if a course is set up to let you learn at your own pace. Add important due dates to a calendar so you do not miss deadlines. Track tasks and assignment deadlines on your phone, in a day planner notebook, or with whatever calendaring tool works best for you.

- Set a schedule and follow a routine. Get up and get ready for the day, follow a regular morning routine (wash up, dress, have some food, coffee/tea, brush your teeth, etc). Having a regular structure to your day will help you keep on track.

- Stay organized. Keep a calendar of tasks and deadlines. Have your course materials and notes in one place so you use your time for learning, not searching for course materials.

- Be kind to yourself. If you find yourself suddenly thrust into a remote learning situation, expecting high productivity is expecting too much of yourself and can exacerbate stress. Set reasonable goals and communicate with your instructors about your progress and challenges.

Keeping on Task

For keeping on task, try the pomodoro technique. This time management technique is especially useful if you find yourself easily distracted. The technique was created by Francesco Cirillo when he was a university student.

Pomodoro sets aside time for focusing on a specific task and rewards you with small chunks of time to be used for short breaks. There are six steps in the original technique:

- Decide on the task to be done.

- Set a timer for 25 minutes.

- Work on the task.

- End work when the timer rings and put a checkmark on a piece of paper.

- If you have fewer than four checkmarks, take a short break (3--5 minutes), then go to step 2.

- After four pomodoros, take a longer break (15--30 minutes), reset your checkmark count to zero, then go to step 1.

Gather Your Accounts

Learning online will likely require you to use technology and tools that you have not encountered in traditional, in-person learning environments or may not be familiar to you in your work environment. As we have discussed in previous modules, planning is critical for successful online learning. This holds true for planning your technology.

Ideally before you begin an online course, organize all the technology required. This information should be provided to you in the course syllabus or other materials provided by the instructor or institution where you are learning.

- Accounts and Applications. You may need to download and install video conferencing software for live lectures, such as Zoom, Webex, BlueJeans or Shindig. Do this well before the first lecture so you have enough time to create an account (if necessary) and test the software. Course assignments may need to be uploaded to a cloud service, such as Google Drive, Dropbox or Microsoft OneDrive. Make sure you have the required account details (username and password) or access information in advance of an assignment deadline. Your university or employer may also use a learning management system (LMS) for delivering online learning, such as Canvas, Blackboard, Moodle, or Sakai. Make sure you have the required account details (username and password) and that you are enrolled in the correct title and section of the course or courses.

- Hardware. Collect and keep handy any power cords, USB cables and extra devices like a computer mouse, keyboard you may need. If possible, store these items in the same place you have designating for studying.

- WiFi vs Wired. If possible, minimize your reliance on wifi by using an ethernet cable. It is also good practice to download course materials to work on assignments offline in case you lose your internet connection or have limited bandwidth. Many online courses and platforms work on mobile (i.e. phone, tablet), too, but others do not. Have a plan for Internet access.

Learning Strategies: Self-regulation and Learning

Metacognitive Strategies

As we have previously discussed, staying motivated and on task while learning online can be difficult without the structure of an on campus course schedule or regular, live interaction with peers and instructors. Perhaps even more so than in traditional, in-person learning environments, to achieve your goals in an online learning environment you need to employ strong self-regulation learning strategies.

Self-regulation refers to the ability to regulate one's thinking and actions. We demonstrate self-regulation when we consider our thought processes and behaviors, and adjust our thinking and actions to achieve desired outcomes.

Self-regulation is a broad topic, but in this module we will focus on three processes you can apply to improve learning: metacognitive, motivational and behavioral. These are key components not only for successful learning, but can apply to any goal or challenge you face in life.

Metacognition is an awareness and understanding of one's own thought process. Applied to learning, it means being aware of and intentional about how you think and learn, and involves planning, monitoring and evaluating your learning progress.

The process starts by assessing what you know and what you don't know, planning for how you are going to do to learn what you don't know, and then evaluating your learning progress and making necessary adjustments.

When you are learning a new topic or skill, ask yourself the following questions. You might consider writing down your answers.

- What tasks do I need to complete or topics do I need to cover? (Try: Review the assignment, scan the chapter, read through the quiz before answering.)

- What do I already know about this topic? (Try: Write down familiar terms, review a previously completed assignment about the topic.)

- What is new to me or, based on past experience, what will be difficult for me to learn? (Try: Formulate questions to answer as you read, plan extra time to spend on difficult topics.)

- What approach will I use to learn this material? (Try: Choose a note-taking technique, make flash-cards, draw a mind map.)

- How will I assess if I have learned the material? (Try: Teach a friend, take a practice quiz.)

Motivational and Behavioral Strategies

Staying motivated, especially through challenging tasks, is difficult for everyone. But part of building strong self-regulation skills is practicing motivational techniques. Below are several strategies to try to keep yourself motivated and moving forward.

- Be SMART. We all know that making goals is a good thing, but we also know that reaching our goals is hard. A common reason why goals are often not achieved is because the goal itself was too vague or too big. A popular technique for making goals we can reach is called SMART, which stands for Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-Based.

- Be as specific as possible when making a goal.

- Have a way to measure your goal so you can track progress.

- Create a goal you can reasonably attain with the resources you have today.

- Keep the goal relevant to your overall values or aligned with the direction you wish to go.

- Set the time or date at which you hope to accomplish your goal.

- Effort not ability. We often get in the way of our own progress and success by giving up because we believe we don't have the natural talent or inherent ability to learn a new skill or concept. Stanford University physiologist Dr. Carol Dweck calls this way of thinking a fixed mindset and it is contrary to the reality for most human beings. Success, for even the best athlete, musician or scientist, requires effort and practice. Believing that we can improve through trial and error, through effort and practice is called a growth mindset. When you feel like quitting, put in a few more minutes or a bit more effort and see if you can push past the desire to give up.

- Hardest thing first. When we are rested and have an alert, fresh mind, we are more likely to push through challenging tasks than when we are tired and spent. Given this, it is better to start with a hard task than to save it for last. You have more energy to devote to the thing that needs it most. And when you complete it, you will feel accomplished, perhaps even exhilarated. This good feeling can propel you to keep going on to the next, less difficult, task.

- Little rewards. You may recall from the previous modules about self-care and time management, taking breaks is important to staying motivated and energized. Consider sweetening your breaks by treating yourself to something you really enjoy; a small reward for putting in a strong effort. For example, eat a piece of chocolate, turn up the music and sing along to your favorite song, or spend a few minutes on social media (but set a timer so you don't fall down the rabbit hole!).

Has someone ever said any of the following statements to you?

- You are what you do, not what you say

- Actions speak louder than words

- Get our act together

- Show, don't tell

As harsh as it may be to hear, there is truth in those statements about the power of behavior. We can aspire to accomplish many things, set goals and create plans, but until we start actually working on achieving our goals, putting our plans into action, we will never leave the starting line.

The final strategy for building self-regulation skills is to be aware of and, when needed, change our behavior in order to achieve our learning goals. But it can be difficult in the moment when we are focused on learning new and challenging material, to be cognizant of our actions. Below are a few techniques to bring mindfulness and intention to our learning behaviors so that we keep doing what works and change what doesn't.

Keep a study log. In addition to tracking when and for how long you study, consider tracking how you study. For example, if you plan a 30 minute study session, stop after 25 minutes and dedicate 90 seconds to taking notes in a study journal on what you did. While you were watching a recorded lecture, did your mind wander? Did you check social media? Did you rewind the video once, twice or several times because you missed or didn't understand something.

Try it a different way. If you use a highlighter while reading a textbook, try instead to focus on only reading and then write a summary of the pages you read. If you usually watch the lecture first and then try the practice problems, reverse the order. Did you concentrate more or less on the lecture when you knew what you needed to look for after reviewing the practice problems?

Never miss twice. A popular mantra for building good habits and behaviors is the "never miss twice" rule. The underlying concept here acknowledges that we are not perfect, but that doesn't mean we should give up entirely. Sometimes we are going to skip a planned study session or miss an assignment deadline. That is okay. To stay on track, don't focus on what you missed. Instead, focus on NOT missing the next study session or assignment deadline.

Practice, Application, Reflection

To ensure that your newly learned knowledge and skills endure, it is important to repeatedly practice new skills, apply knowledge in different contexts, and reflect on what you have learned. A well-designed learning experience will provide you with opportunities to practice, apply, and reflect, but you can reinforce your learning outside of a class by connecting it to your everyday life and work.

Here's a selection of valuable learning strategies to try:

- Keep a learning journal. Regularly reflect on our learning by writing down thoughts and questions that arise. Write daily or weekly summarizing of what you are learning, perhaps like you are writing a letter or text to a friend.

- Retrieval practice. Every time you have to remember something, you deepen your memory of that something, which makes it easier and quicker to recall later. This is especially important with new information or knowledge that is early in the encoding process. Create opportunities to recall newly learned concepts or skills. Flashcards are a popular method of retrieval practice.

- Ask yourself why. It is common in online learning environments that instructors allow you to try to answer questions multiple times. These practice problems or formative quizzes and knowledge checks are good at providing instant feedback if you are right or wrong. But a lucky guess won't be easily remembered. Even if you get the answer right on the first try, make sure you understand why your answer is correct.Share with us learning and study strategies that you find useful. Is there a specific practice that's especially challenging or especially rewarding?

- Make connections. Drawing connections between new material you're learning and your prior knowledge or experiences is an effective way to deepen learning. For examples, identify real life examples of concepts from your course; recall related concepts from prior learning materials; review your notes from previous sessions before you learn new material; or summarize main ideas and concepts using examples not provided in the learning materials, but that you imagine.

In the discussion forum below, share with us learning and study strategies that you find useful. Is there a specific practice that's especially challenging or especially rewarding?

Effective Reading Comprehension

Have you ever read a paragraph or few pages and thought, "what did I just read." Your eyes passed over the words, but you don't remember a thing. Now you need to re-read the passage, which is 10 more minutes of studying that you don't have to spare.

The act of reading does not guarantee successful comprehension or knowledge retention. But fear not! Even if you first learned how to read decades ago, you can still become a better, more efficient and effective reader.

One enduring technique developed by Francis P. Robinson, an American education philosopher in his 1946 book Effective Study, is call SQ3R. This acronym stands for Survey, Question, Read, Recall, and Review. It may require practice to use effectively, but it is well worth the effort. The steps for SQ3R are as follows:

- First, skim or survey through your material to get a high level idea of the content.

- List out several questions you have about the content.

- Go back and read thoroughly, but this time try to answer the questions you listed.

- Next, recall from your memory what you just learned. Pretend you are telling someone about what you have just read.

- Review the material with a closer focus. Were you able to answer your questions? Did new questions arise? If so, repeat the process to try answering your new questions.

Another method for boosting comprehension and knowledge retention is to make annotations to the learning material while reading. Add notes, mark down thoughts and comments, list out questions, and make connections as you are reading. Using this technique will help you make sense of complicated materials, but will also organize your notes for reviewing later.

- Read the material once through and mark unfamiliar concepts or words, and identify the key ideas. Pose questions.

- Read the material again, making more detailed notes this time. Mark ideas you agree and disagree with.

- Make connections to other things you have read, studied or experienced. Highlight key phrases and ideas and rewrite them in your own words. Add personal comments.

Video Comprehension Techniques

The reading comprehension and retention techniques we just reviewed can also apply to recorded video lectures, which you can rewatch, slow down or speed up as you take notes. Below are additional tips for getting the most out of online learning videos.

Recorded Video Lectures

For recorded video, pause and write a brief summary of what you have heard every few minutes. You can pause the video or review as many times as you want. If the instructor has provided PowerPoint slides along with the video, consider downloading or printing them out, and take notes directly on the slides.

It may be helpful to turn video captions on, to read along and help with your note taking. (And if you're listening to an audio only recording, follow along with the transcript.) Both captions and a transcript will help provide details that may be missed with just watching or listening.

Live Video Lectures

For live video lectures delivered in video conferencing software like Zoom, avoid taking notes. Pay attention to what you are hearing and participate in the live discussion to help keep your focus. Raise your virtual hand or ask a question in the chat. Ask if the video lecture is being recorded so you can review and take detailed notes later.

Take advantage of video conference break-out groups, if offered. These live, small group discussions will give you a chance to hear other perspectives or review challenging material as a group.

Finding your peers

Recall in the Self-Care for Learning module we discussed the importance of making time for family and friends to keep us grounded and energized. Fostering social connection with your instructor and classmates is also important to your learning.

Your experiences may vary with synchronous or asynchronous instruction in your courses, but in any context, online learning can be incredibly vibrant when learners connect with one another. Ways to connect will depend on the structure and technology used in the course, but a few common methods for connection include:

- introducing yourself in the discussion boards, like we asked you to do for this course

- providing constructive comments on peer and group assignments

- participating in live lectures and discussions via video conferencing applications (e.g. Zoom, Webex, BlueJeans, Shindig, Google Hangouts)

There are also many opportunities to connect beyond the learning management system (LMS) used for your course. See if your instructor has created a private group on social media sites like Facebook or LinkedIn. Perhaps there is a Twitter hashtag for continued conversation outside of the course. You might also consider finding a study buddy or a study group to help build connections and community in your course. This will not only alleviate isolation, but also promote collaborative learning.

In the discussion forum below, share ideas for connecting to your learning peers and the tools, apps and technology you like to use for connecting online.

Communication

When learning online, particularly in an asynchronous course that does not include regular, live interaction with your instructor or peers, it is a good practice to over communicate. This may mean regular email checkins with your instructor, reading and responding to discussion forum posts, or text chatting with study buddies. No matter how you communicate, it is important to be kind and patient to yourself and others. Give and expect respect, especially during asynchronous communication like discussion boards and email since it can be easy to misconstrue someone's meaning. Like you, your peers are real people. Do your part to foster a respectful, supportive community.

Tips for Keeping in Touch:

- Keep your instructor informed. Self-advocate by asking your instructor for help when you need it. Let them know if you are ill, unable to log on, need an extension on an assignment, etc.

- Reflect and chat with peers. Share your learning goals, study tips, additional resources relevant to the course, something that makes you laugh, music you love, etc.

- Assume good intent. Everyone is trying their best. Emails and text-based discussions do not have the verbal and visual cues you're used to seeing to inform your reaction and interpretation.

Collaboration

Collaboration and group work in an online learning environment can be a very rewarding experience. Working together helps you improve communication skills and strengthen your knowledge of a topic by incorporating others' points of view. Learning to manage tasks as a group and collaborate efficiently and effectively are also important workplace skills.

Getting Started. If group work assignments are a component of your course, start by carefully reviewing the assignment details to make note of major tasks and requirements. Take time to get acquainted with your teammates, whether your team is determined by your instructor or you are tasked with finding a team. Discuss the project with your team and make sure everyone in the group understands the assignment fully.

Planning. As with anything, have a solid plan.

- List out the tasks required and the steps to achieve those tasks.

- Assign roles and tasks. Decide upon a leader to keep the group members on schedule and accountable to deadlines.

- Create a schedule. Work backwards from the project due date to determine realistic deadlines for milestones and associated tasks.

Choose technology for collaboration. You and your team should choose technology and tools that allow easy communication and collaboration for all team members. Be sensitive to the limitations team members might have, including Internet access, video and audio capabilities, cloud services that may require a subscription fee, and privacy concerns. There are a range of free or paid options. Your instructor may have suggestions or requirements as to what you and your team should use.

Communicating. Practice active listening and supportive communication with your teammates. Offer constructive and actionable feedback, not just criticism and negative comments. Make suggestions to group members that may need help, but resist doing their tasks for them. Address issues within the group early, and communicate any issues that can't be resolved by the group to your instructor.

Thank you for joining us for this short book "How to Learn Online".

I wish you all the best as you pursue your learning goals.

REFFERENCES

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Population Health. (2016, July 15). CDC - Sleep Hygiene Tips - Sleep and Sleep Disorders. Retrieved June 15, 2020, fromhttps://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html

- 2. A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2019. Can't sleep? Try these tips. Updated August 3, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2020. Available from:https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000853.htm

- 3. National Institute on Aging (NIA). (2016, May 1). A Good Night's Sleep. Retrieved June 15, 2020, fromhttps://www.nia.nih.gov/health/good-nights-sleep

- 4. American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). (2015, December 15). Chronic Insomnia: What You Can Do to Sleep Better. Retrieved June 15, 2020, fromhttps://www.aafp.org/afp/2015/1215/p1058-s1.html

- 5. Koulivand, P. H., Khaleghi Ghadiri, M., & Gorji, A. (2013). Lavender and the nervous system. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2013, 681304.https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2013/681304/

- 6. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). (2011, September). In Brief: Your Guide to Healthy Sleep. Retrieved June 15, 2020, fromhttps://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/public/sleep/healthysleepfs.pdf

- 7. A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2019. Changing your sleep habits. Updated April 15, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2020. Available from:https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000757.htm

- 8. Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School. (2007, December 18). The Drive to Sleep and Our Internal Clock | Healthy Sleep. Retrieved June 15, 2020, fromhttp://healthysleep.med.harvard.edu/healthy/science/how/internal-clock

- 9. National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO). (n.d.). Recommended Light Levels. Retrieved June 15, 2020, fromhttps://www.noao.edu/education/QLTkit/ACTIVITY_Documents/Safety/LightLevels_outdoor+indoor.pdf

- 10. Zandy, M., Chang, V., Rao, D. P., & Do, M. T. (2020). Tobacco smoke exposure and sleep: estimating the association of urinary cotinine with sleep quality. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 40(3), 70--80.https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/health-promotion-chronic-disease-prevention-canada-research-policy-practice/vol-40-no-3-2020/tobacco-smoke-exposure-sleep-study.html

- 11. Lichstein, K., Taylor, D., McCrae, C., & Thomas, S. (2010). Relaxation for Insomnia. In M. Aloia, B. Kuhn, & M. L. Perlis (Eds.), Behavioral Treatments for Sleep Disorders: A Comprehensive Primer of Behavioral Sleep Medicine Interventions (Practical Resources for the Mental Health Professional) (1st ed., pp. 45--54). Retrieved fromhttps://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/assets/user-content/documents/Lichstein_RelaxationforInsomnia-BTSD.pdf

- 12. Jerath, R., Beveridge, C., & Barnes, V. A. (2019). Self-Regulation of Breathing as an Adjunctive Treatment of Insomnia. Frontiers in psychiatry, 9, 780.https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00780/full

- Bokcenter.harvard.edu. 2020. How Memory Works. [online] Available at: [Accessed 20 November 2020].

Follow Instagram @kompasianacom juga Tiktok @kompasiana biar nggak ketinggalan event seru komunitas dan tips dapat cuan dari Kompasiana. Baca juga cerita inspiratif langsung dari smartphone kamu dengan bergabung di WhatsApp Channel Kompasiana di SINI