Keynes' general wisdom regarding fiscal policies is to adopt countercyclical measures in response to fluctuating economic cycles: contractive during periods of boom to avoid overheating the economy and expansive during periods of recession to bolster economic activity. However, due to frequent external shocks as a consequence of increasingly complex global economic integration, emerging markets and developing economies -- especially commodity exporters -- tend to amplify the fluctuating cycle, by implementing procyclical fiscal policy. The degree of fiscal procyclicality in commodity dependent countries is twice above non commodity exporters (World Bank, 2023). How can these countries fail to control the supposedly stabilizing 'fiscal' measures? How much of an impact can it bring towards countries' economy? What does this imply for commodity exporters? It turns out that political-economy pressures as well as credit inability in worsening economic situations could be key to explaining this fiscal spiraling phenomenon.

Stabilizing the economy

Fiscal policy is the use of government spending and taxation to influence the economy (IMF, 2022). Fiscal policy is often used by governments to encourage robust, long-term growth and to lower poverty. Prior to the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, monetary policy played a more prominent role in macroeconomic stabilization. However, during the GFC, liquidity traps suffered by big economies like the US, Europe, and Japan made monetary weapons less effective -- leading to no choice but to conduct a fiscal policy expansion. After the GFC, countercyclical fiscal policy has become more eminent, especially in matters of stabilizing macroeconomic conditions.

ECB chief economist Philip Lane stated how countercyclical fiscal policy is preeminent. First, it could boost the economy during a downturn and prevent it from overheating during a boom. It is a responsible option given that it is unclear if the crisis will be a temporary or lasting shock. Second, a countercyclical fiscal policy, by requiring the government to limit spending during a boom, could contain the absolute level of spending due to political economy factors like corruption. Third, the automatic stabilizer component of a government budget allows it to pursue countercyclical fiscal policy (Lane, 2002). However, it remains the issue that developing countries that export resources as its main source of revenue still tend to adopt procyclical fiscal policy.

Stabilizing? Not entirely

For emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), it is still the case that procyclical policy amplifies an already volatile business cycle (more emphasis on emerging markets).

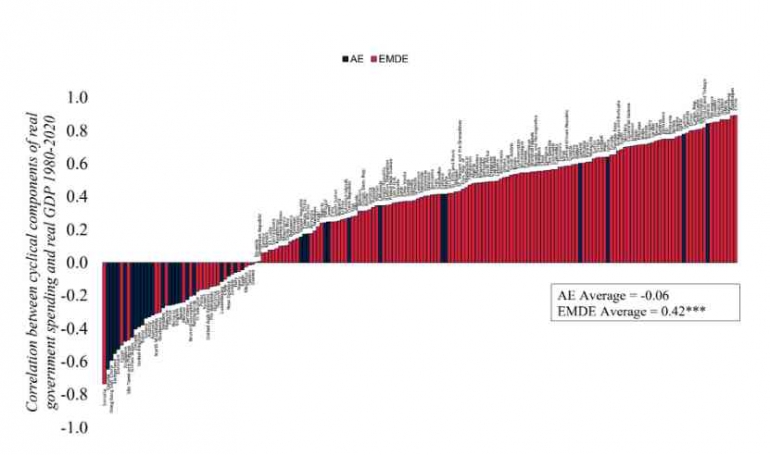

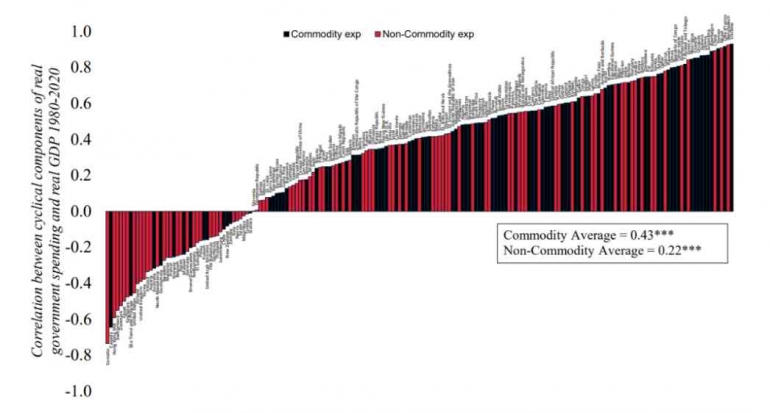

Figure 1 shows the correlations for the procyclical components of GDP and government spending for 189 countries, mixed between advanced and developing economies, from 1980 until 2020. This visual representation is undoubtedly salient, as we can see a dominating amount of positive correlation (indicating procyclicality) in developing countries. An even more striking correlation is shown between commodity exporters and non-commodity exporters in this regard. Figure 2 reveals that the association between the cyclical components of real government spending and real GDP for commodity exporters is twice as great as that for non-commodity exporters (0.43 compared to 0.22, both highly significant). The result still holds in 3 main commodities exported, namely agriculture, metals, and energy, which means that commodity exporters, regardless of their major commodity export, are more likely to deploy procyclical fiscal policy in response to booms and busts.

How does this happen? Government spending frequently spirals out of control in prosperous times, leading to the inability to borrow in difficult times which doubles its volatility and hurts the economy for commodity dependent EMDEs. In contrast to what Keynes envisioned as a stabilizing tool, fiscal policy thus became a source of instability for certain countries (World Bank, 2023).

Given the notable reaction of fiscal variables to commodity shocks, the function of fiscal policy as a potential source of macroeconomic instability is particularly pertinent in commodity exporters. This analysis is evident in an early policy analysis comparing five developing countries (Colombia, Cameroon, Kenya, Nigeria, and Jamaica) when facing commodity price booms in 1970. Fiscal authorities in Kenya, Nigeria, and Jamaica all lost control over public finances, resulting in a sharp increase in government spending as a percentage of GDP. The increase in spending actually exceeds the growth in revenue, which generally results in increased borrowing from abroad and bigger budget deficits. This lack of budgetary control commonly led to full-blown fiscal crises (Cuddington, 1989).

The game of managing abundance