When I entered FEB UI last year, it seemed to me that the faculty had a strict on-time policy, both in the classroom and outside of it. However, as time went by, I realized that even this acclaimed institute is filled with people who are prone to the very human nature of being late, including myself.

Even though it is merely irritating at the local level, it can do some real damage at the aggregate level of the economy. To provide a picture, a 2006 survey stated that American CEOs' tardiness costs the US economy $90 billion in lost productivity annually while a 2012 study stated that staff lateness costs the British economy 9 billion every year .

Psychology as the study of behavior has offered some explanations as to why people keep doing this, but economics as the study of choice may offer more insight. In this writing, I will present a model that explores what drives a person to become late at coming to an occasion.

Meet the model

The model presented explains how people deviate from being on time for events that have an independent, recurring schedule. In other words, no matter what time people come, the event that happens repeatedly begins at a certain time, uninfluenced whether its attendants come early or late. Seminars, movie screenings, public transportation departures, and classes are examples of events possessing such characteristics.

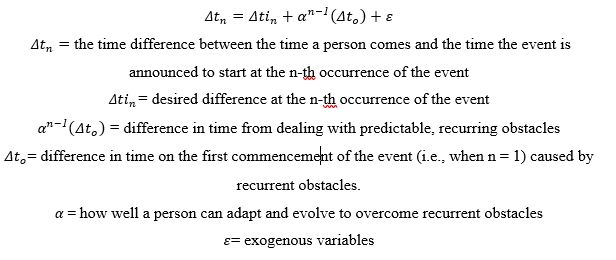

As can be seen in the equation below, the model explains that the time difference between the time a person comes and the time the event is announced to start at the n-th occurrence of the event is the sum of her "desired difference", difference in time from how well she negotiates predictable obstacles hindering her, and exogenous residuals. An avid reader of mathematics may recognize this model as a difference equation. Note that the two first variables are a function of n, meaning that its value may change over time. Therefore, this model not only explains how late (or early) a person can be, but it can also explain how that person adjusts her arrival time intertemporally.

To understand the meaning of "desired difference" (ti(n)), a harsh truth must be grasped: people intentionally do not come on time, let alone come early. Granted, there are good benefits from coming before the event kicks in; after all, an early bird can catch a lot of "worm", such as common goods offered in the event (like a strategic back seat). However, being early incurs an opportunity cost as one can do something else instead of waiting for the event to start, like get more bedtime before a morning class. In addition, Durayappah (2014) highlighted the fact that being early can be uncomfortable and impolite.

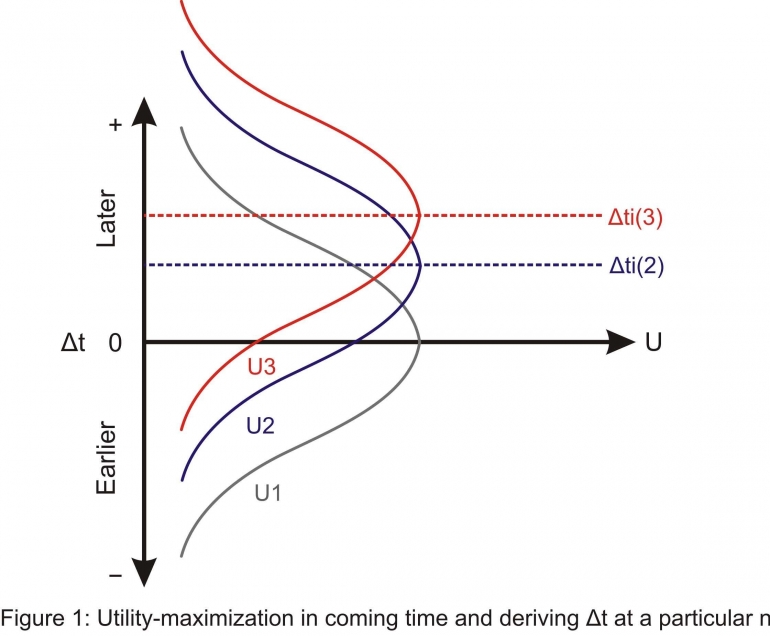

A utility-maximizing person may seek to come in late, up to the point where the utility from being late for an additional minute is equal to the perceived loss of utility from missing the event for that additional minute, as demonstrated in Figure 1 below. If the event is perceived to be on time, then people will seek to come on time like in U1. However, if the utility from the event is perceived to trickle only after some time has elapsed, such as in a cinema where the movie only rolls after some advertisement, then do not be surprised if people seek to come in late, as shown in U2. Based on that assumption, participants to an event do not necessarily have a desire to come at the time its organizers tell them to come.

She then lives up to her name, and when she comes to the next general lecture, she will shift her expectations to U2. If the lecturer is still late, then she might shift her expectations further to U3 and have a bigger desired difference when she attends the event for the third time. For the purpose of simplifying the discussion, it is assumed that the desired difference is upward sloping, although it can take many forms.